For the past few weeks, I have been considering what recent research has to say about the evolution of the dual-layer aka customizable pathways design. A lot of this research is, unfortunately, still locked up in my dissertation, so time to get to publishing. But until then, here is kind of the run down of where it has been and where it is going.

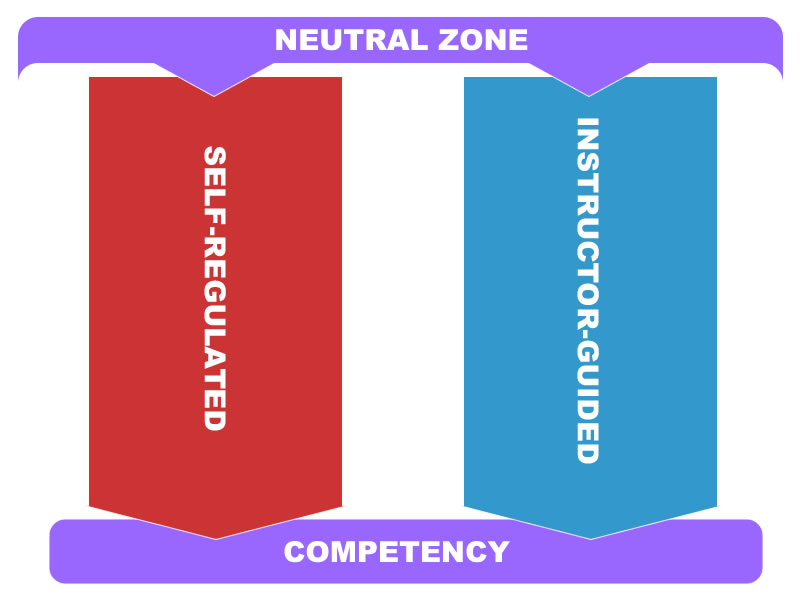

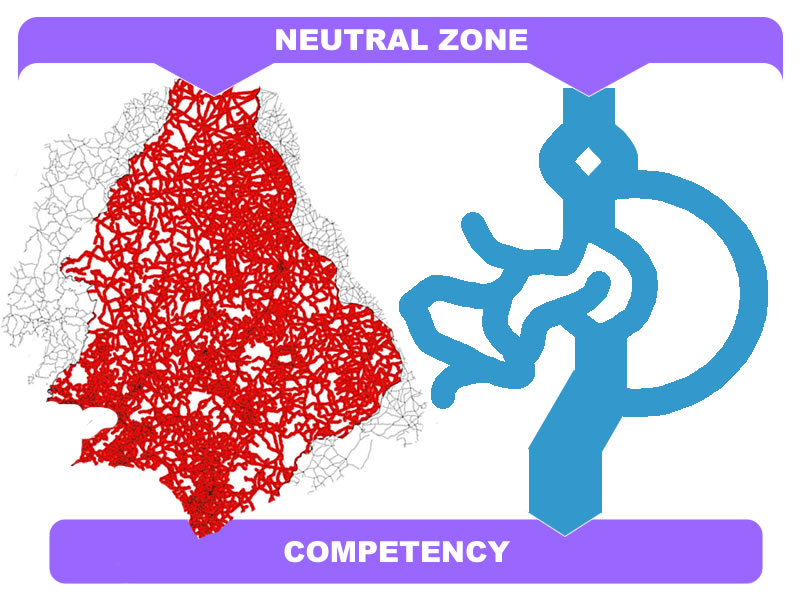

The original idea was called “dual-layer” because the desire was to create two learning possibilities within a course: one that is a structured possibility based on the content and activities that the instructor thinks are a good way to learn the topic, the other an unstructured possibility designed so that learners can created their own learning experience as they see fit. I am saying “possibility” where I used to say “modality.” Modality really serves as the best description of these possibilities, since modality means “a particular mode in which something exists or is experienced or expressed.” The basic idea is to provide an instructivist modality and a connectivist modality. But modality seems to come across as too stuffy, so I am still looking for a cooler term to use there.

The main consideration for these possibilities is that they should be designed as part of the same course in a way that learners can switch back and forth between them as needed. Many ask: ‘why not just design two courses?” You don’t want two courses as that could impeded changing modalities, as well as create barriers to social interactions. The main picture that I have in my head to explain why this is so is a large botanical garden, like this:

There is a path there for those that want to follow it, but you are free to veer off and make your own path to see other things from different angles or contexts. But you don’t just design two gardens, one that is just a pathway and one that is just open fields. You design both in one space.

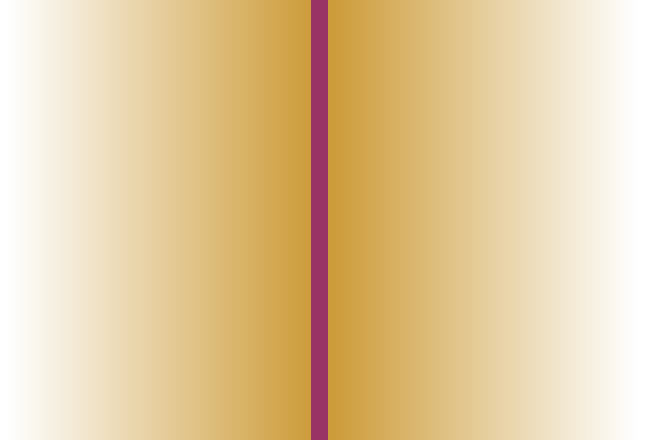

So in other words, you design a defined path (purple line below) and then connect with opportunities to allow learners to look at the topic from other contexts (gold area below):

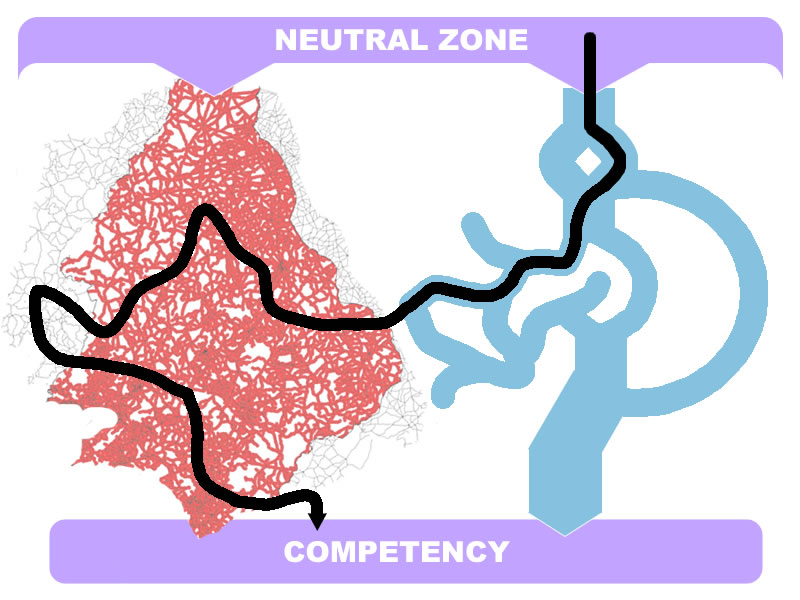

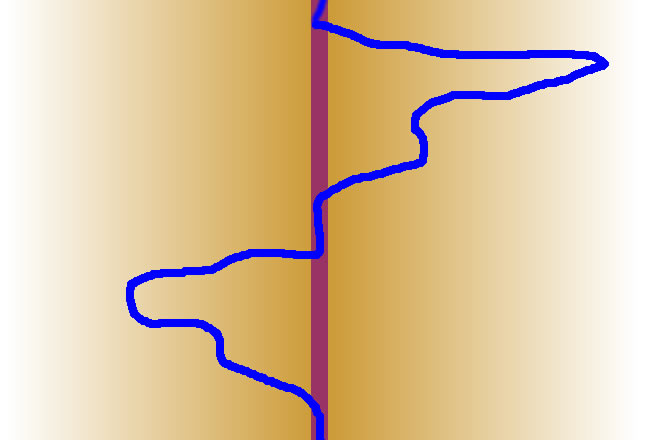

You have a defined modality (the path), and then open up ways for people to go off the path into other contexts. When allowed to mix the two, the learner would create their own customized pathway, something like this:

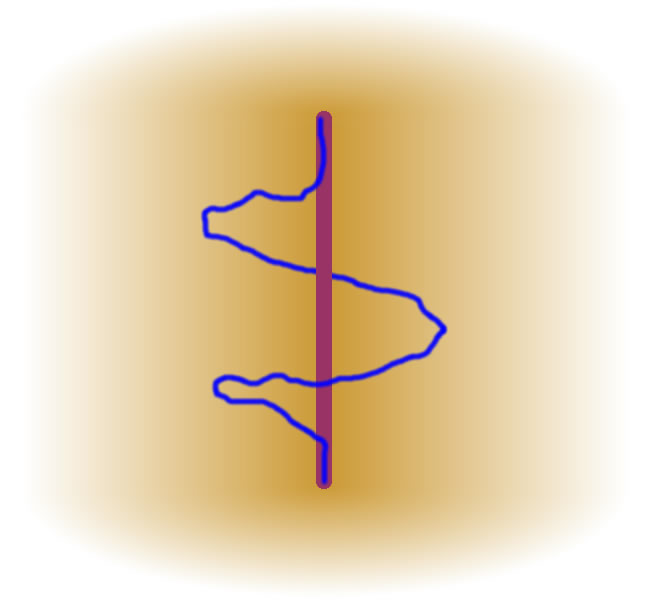

The problem with the image above is that this really shouldn’t only be about going off the walkway in the garden to explore other contexts. Learners should be allowed to dig under the walkway, or fly above it. They should be able to dig deeper or pull back for a bird’s eye view as needed. So that would take the model into a three dimensional view like this:

(please forgive my lack of 3-D modeling skills)

Learners can follow the instructors suggested content or go off in any direction they choose, and then change to the other modality at any moment. They can go deeper, into different contexts, deeper in different contexts, bigger picture, or bigger picture in different contexts.

The problem that we have uncovered in using this model in DALMOOC and HumanMOOC is that many learners don’t understand this design. However, many do understand and appreciate the choice… but there are some that don’t want to get bogged down in the design choices. Some that choose one modality don’t understand why the other modality needs to be in the course (while some that have chosen that “other” modality wonder the same thing in reverse). So really, all that I have been discussing so far probably needs to be relegated to an “instructional design” / “learning experience design” / “whatever you like to call it design” method. All of this talk of pathways and possibilities and modalities needs to be relegated to the design process. There are ways to tie this idea together into a cohesive learning experience through goal posts, competencies, open-ended rubrics, assignment banks, and scaffolding. Of course, scaffolding may be a third modality that sits between the other two; I’m not totality sure if it needs to be its own part or a tool in the background. Or both.

The goal of this “design method” would be to create a course that supports learners that want instructor guidance while also getting out of the way of those that want to go at it on their own. All while also recognizing that learners don’t always fall into those two neat categories. They may be different mixtures of both at any given moment, and they could change that mixture at any given point. The goal would be to design in a way that gives the learner what they need at any given point.

Of course, I think the learner needs to know that they have this choice to make. However, going too far into instructivism vs. connectivism or structured vs. unstructured can get some learners bogged down in educational theory that they don’t have time for. We need to work on a way to decrease the design presence so learners can focus on making the choices to map their learning pathway.

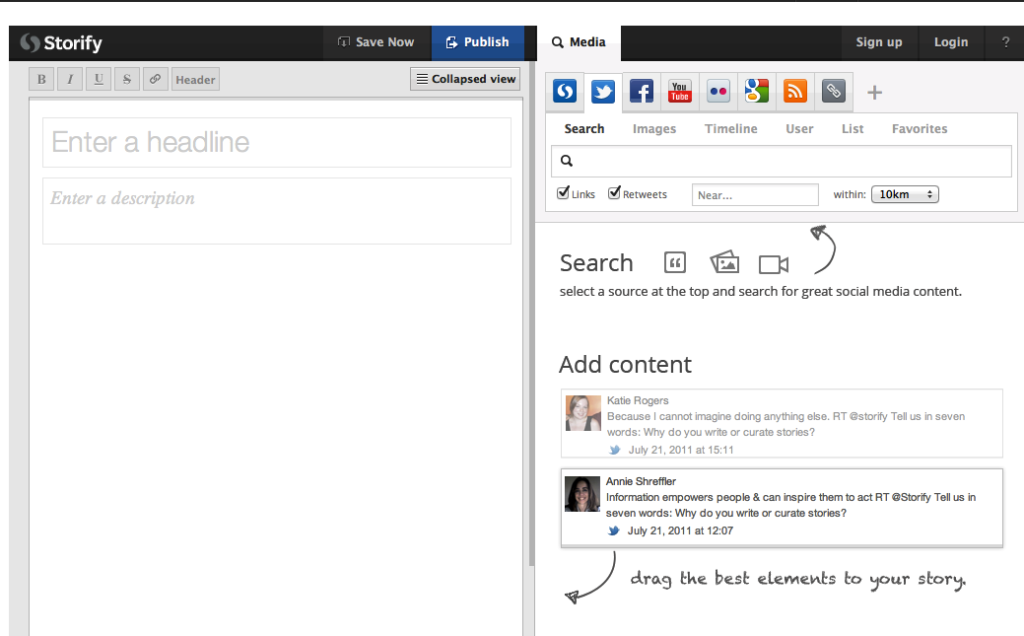

So the other piece to the evolution of this pathways idea is creating the tools that allow learners to map their pathway through the topic. What comes to mind is something like Storify, re-imagined as a educational mapping tool in place of an LMS. What I like about Storify is the simple interface, and the way you can pull up a whole range of content on the right side of the page to drag and drop into a flowing story on the left.

I could image something like this for learners, but with a wide range of content and tools (both prescribed by the instructor, the learner, other learners, and from other places on the Internets) on the right side. Learners would drag and drop the various aspects they want into a “pathway” through the week’s topic on the left side. The parts that they pull together would contain links or interactive parts for them to start utilizing.

For example, the learner decides to look at the week’s content and drags the instructor’s introductory video into their pathway. Then they drag in a widget with a Wikipedia search box, because they want to look at bigger picture on the topic. Then they drag a Twitter hashtag to the pathway to remind themselves to tweet a specific question out to a related hashtag to see what others say. Then they drag a blog box over to create a blog post. Finally, they look in the assignment bank list and drag an assignment onto the end of the pathway that they think will best prove they understand the topic of the week.

The interesting thing about this possible “tool” is that after creating the map, the learner could then create a graph full of artifacts of what they did to complete the map. Say they get into an interesting Twitter conversation. All of those tweets could be pulled into the graph to show what happened. Then, let’s say their Wikipedia search led them to read some interesting blog posts by experts in the field. They could add those links to the graph, as well as point out the comments they made. Then, they may have decided to go back and watch the second video that the instructor created for the topic. They could add that to the graph. Then they could add a link to the blog post they created. Finally, they could link to the assignment bank activity that they modified to fit their needs. Maybe it was a group video they created, or whatever activity they decided on.

In the end, the graph that they create itself could serve as their final artifact to show what they have learned during the course. Instead of a single “gotcha!” test or paper at the end, learners would have a graph that shows their process of learning. And a great addition to their portfolios as well.

Ultimately, These maps and graphs would need to be something that reside on each learners personal domain, connecting with the school domain as needed to collect map elements.

When education is framed like this, with the learner on top and the system underneath providing support, I also see an interesting context for learning analytics. Just think of what it could look like if, for instance, instead of tricking struggling learners into doing things to stay on “track” (as defined by administrators), learning analytics could provide helpful suggestions for learners (“When other people had problems with _____ like you are, they tried these three options. Interested in any of them?”).

![]() Of course, I realized that I am talking about upending an entire system built on “final grades” by instead focusing on “showcasing a learning process.” Can’t say this change will ever occur, but for now this serves as a brief summary of where the idea of customizable pathways has been, where it is now (at least in my head, others probably have different ideas that are pretty interesting as well), and where I would like for it to go (even if only in my dreams).

Of course, I realized that I am talking about upending an entire system built on “final grades” by instead focusing on “showcasing a learning process.” Can’t say this change will ever occur, but for now this serves as a brief summary of where the idea of customizable pathways has been, where it is now (at least in my head, others probably have different ideas that are pretty interesting as well), and where I would like for it to go (even if only in my dreams).

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.