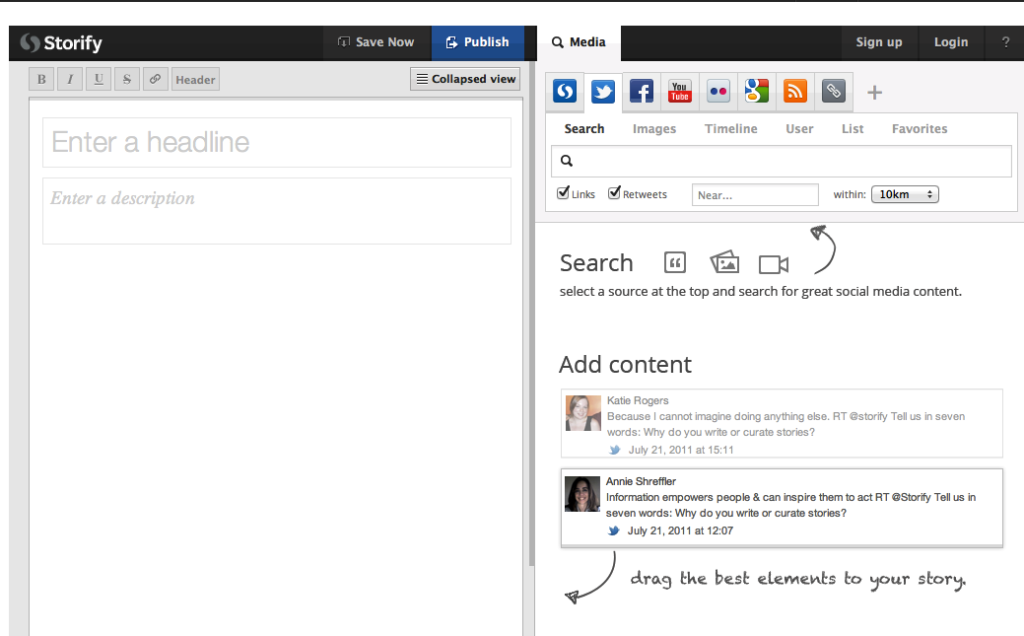

You might have noticed some chatter recently about H5P, which can create interactive content (videos, questions, games, content, etc) that works in a browser through html5. The concept seems to be fairly similar to the E-Learning Framework (ELF) from APUS and other projects started a few years ago based on html5 and/or jquery – but those seem to mostly be gone or kept a secret. The fact that H5P is easily shareable and open is a good start.

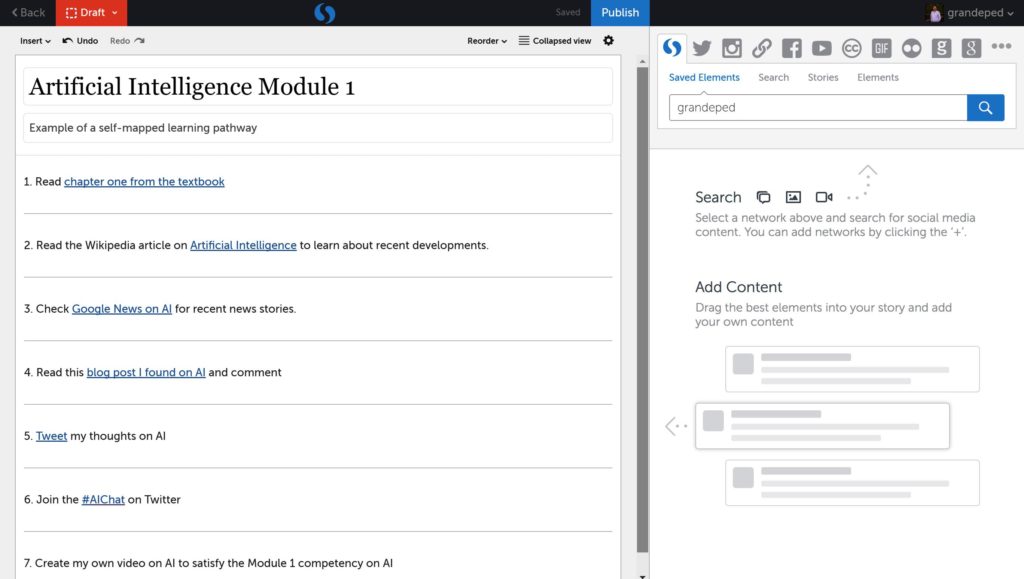

Some of our newer work on self-mapped learning pathways is starting to focus on how to build tools that can help learners map their own learning pathway through multiple options. Something like H5P will be a great tool for that. I am hoping that the future of H5P will include ways to harness AI in ways that can mix and match content in ways beyond what most groups currently do with html5.

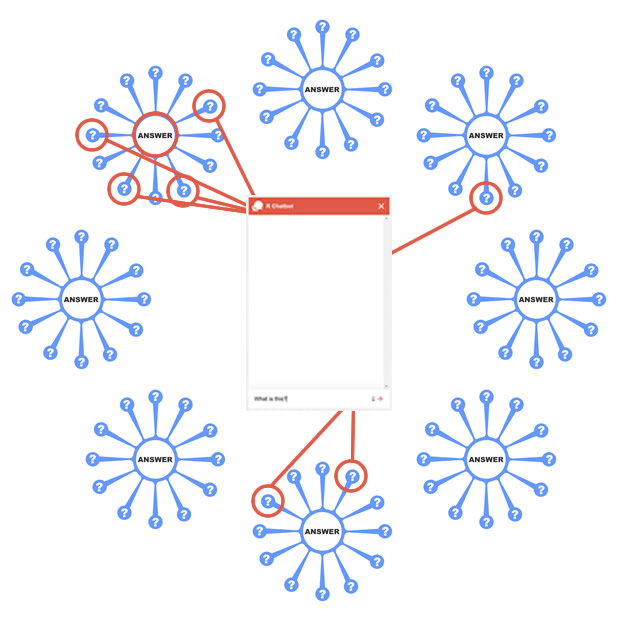

To explain this, let me take a step back a bit and look at where our current work with AI and Chatbots currently sits and point to where this could all go. Our goal right now is to build branching tree interfaces and AI-driven chatbots to help students get answers to FAQs about various courses. This is not incredibly ground-breaking at this point, but we hope to take this in some interesting directions.

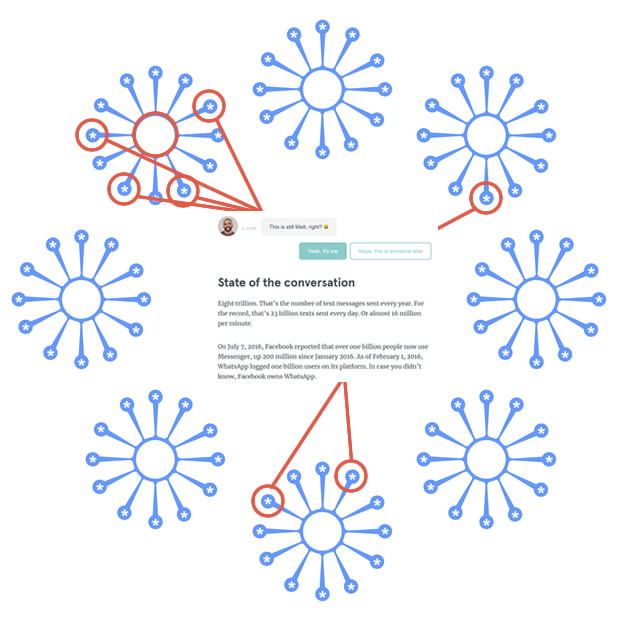

So, the basic idea with our current chatbots is that you create answers first and them come up with a set of questions that serve as different ways to get to that answer. The AI uses Natural Language Processing and other algorithms to take what is entered into a chatbot interface and match the entered text with a set of questions:

Diagram 1: Basic AI structure of connecting various question options to one answer. I guess the resemblance to a snowflake shows I am starting to get into the Christmas spirit?

You put a lot of answers together into a chatbot, and the oversimplified way of explaining it is that the bot tries to match each question from the chatbot interface with the most likely answer/response:

Diagram 2: Basic chatbot structure of determining which question the text entered into the bot interface most closely matches, and then sending that response back to the interface.

This is our current work – putting together a chatbot fueled FAQ for the upcoming Learning Analytics MOOCs.

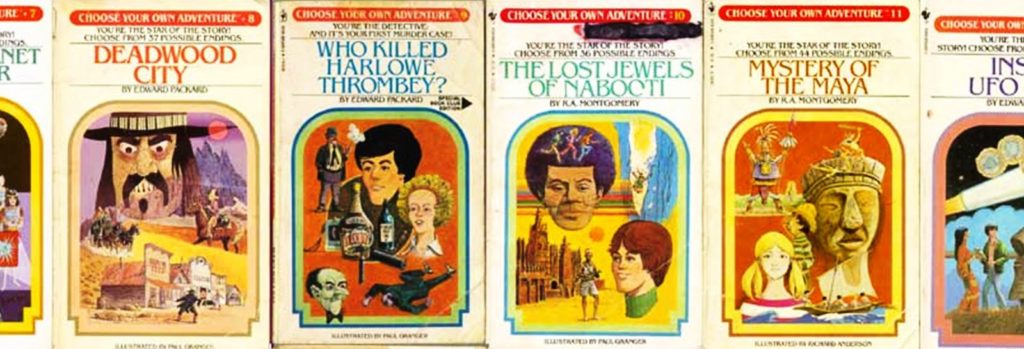

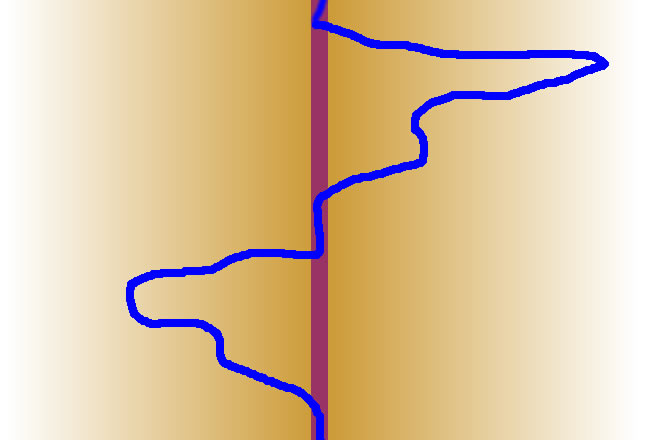

Now, we tend to think of these things in terms of “chatting” and/or answering questions, but what if we could turn that on its head? What if we started with some questions or activities, and the responses from those built content/activities/options in a more dynamic fashion using something like H5P or conversational user interfaces (except without the part that tries to fool you that a real person is chatting with you)? In other words, what if we replaced the answers with content and the questions with responses from learners in Diagram 1 above:

Diagram 3: Basic AI structure of connecting learners responses to content/activities/learning pathway options.

And then we replaced the chatbot with a more dynamic interactive interface in Diagram 2 above:

Diagram 4: Basic example of connecting learners with content/activity groupings based on learner responses to prompts embedded in content, activities, or videos.

The goal here would be to not just send back a response to a chat question, but to build content based on what learner responses – using tools like H5P to make interactive videos, branching text options, etc. on the fly. Of course, most people see this and think how it could be used to create different ways of looking at content in a specific topic. Creating greater diversity within a topic is a great place to start, but there could also be bigger ways of looking at this idea.

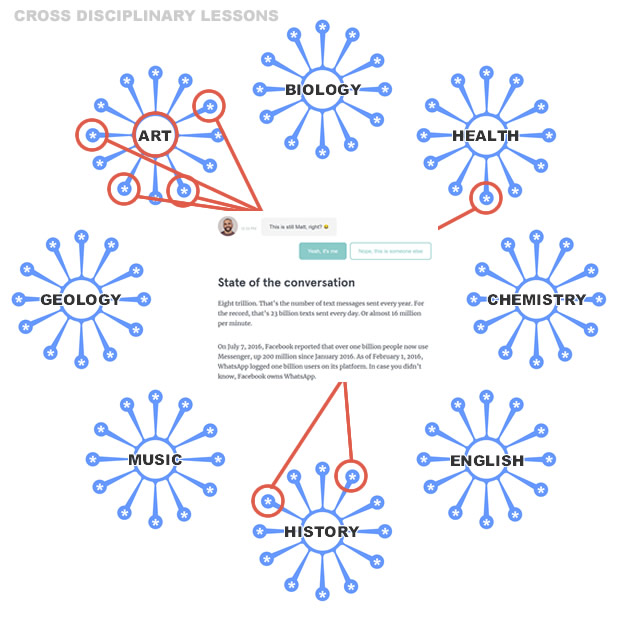

For example, you could look at taking a cross-disciplinary approach to a course and use a system to come up with ways to bring in different areas of study. For example, instead of using the example in Diagram 4 above to add greater depth to a History course, what if it could be used to tap into a specific learner’s curiosities to, say, bring in some other related cross disciplinary topics:

Diagram 5: Content/activity groupings based on matching learner responses with content and activities that connect with cross disciplinary resources.

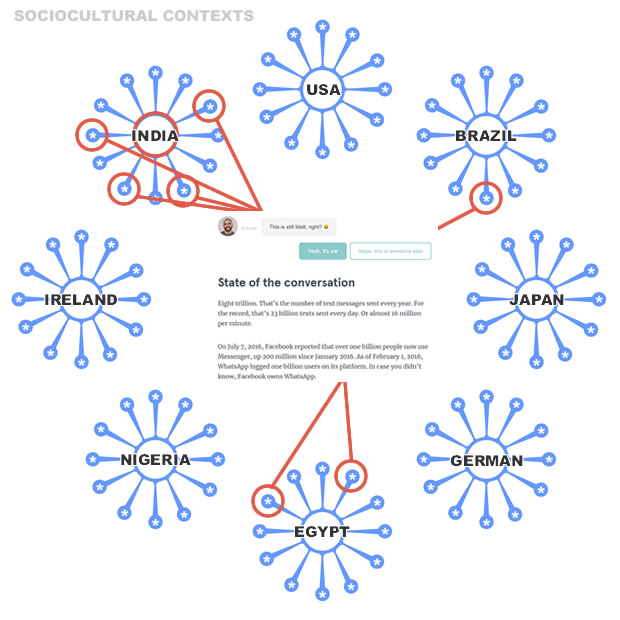

Of course, there could be many different ways to approach this. What if you could also utilize a sociocultural lens with this concept? What if you have learners from several different countries in a course and want to bring in content from their contexts? Or you teach in a field that is very U.S.-centric that needs to look at a more global perspective?

Diagram 6: Content/activity groupings based on matching learner responses with content and activities that focus on different countries.

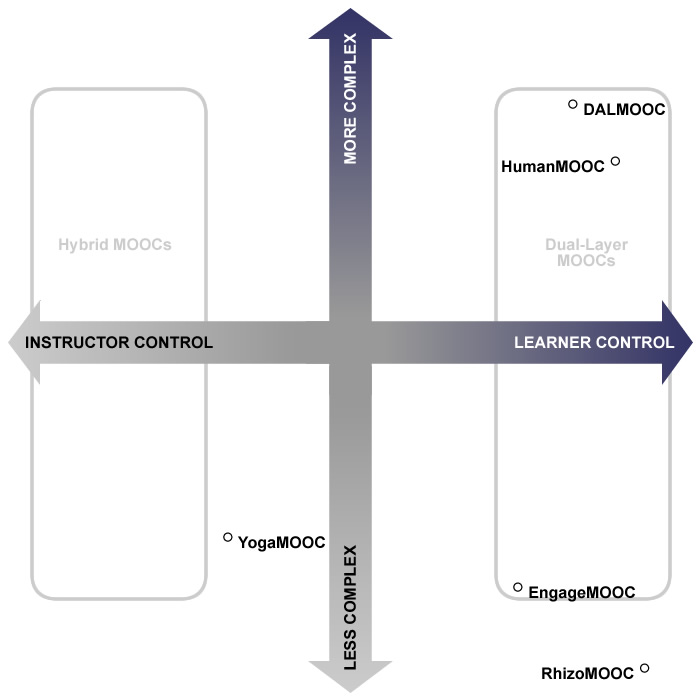

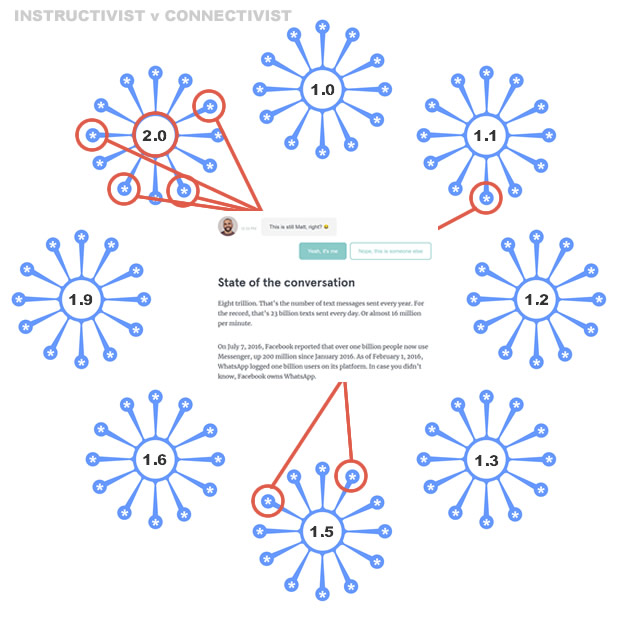

Or you could also look at dynamic content creation from an epistemological angle. What if you had a way to rate how instructivist or connectivist a learner is (something I started working on a bit in my dissertation work)? Or maybe even use something like a Self-Regulated Learning Index? What if you could connect learners with lessons and activities closer to what they prefer or need based on how self-regulated, connectivist, experienced, etc they are?

Diagram 7: The content/activity groupings above are based on a scale I created in my dissertation that puts “mostly instructivist” at 1.0 and “mostly connectivist” at 2.0.

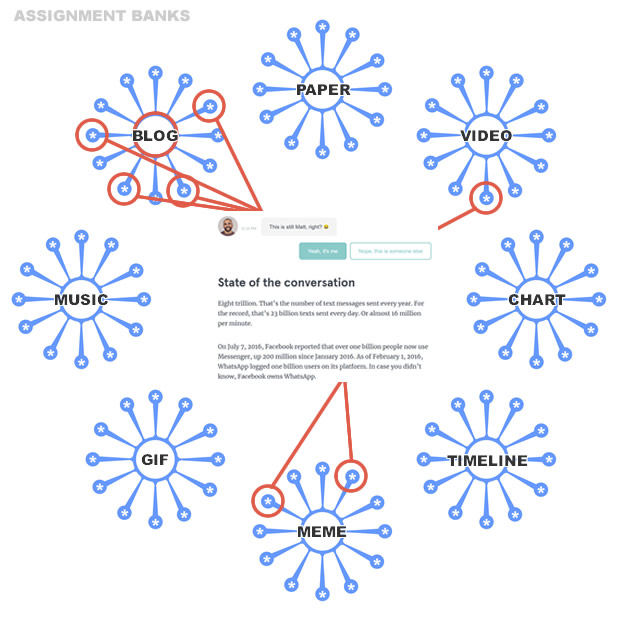

You could also even look at connecting an assignment bank to something like this to help learners get out of the box ideas for how to prove what they have been learning:

Diagram 8: Content/activity groupings based on matching learner responses with specific activities they might want to try from an assignment bank.

Even beyond all of this, it would be great to build a system that allows for mixes of responses to each prompt rather than just one (or even systems that allow you to build on one response with the next one in specific ways). The red lines in the diagrams above represent what the AI sees as the “best match,” but what if it was indicating the percentage of what content should come from which content pool? The cross-disciplinary image above (Diagram 5) could move from just picking “Art” as the best match to making a lesson that is 10% Health, 20% History, 50% Art, and so on. Or the first response would be some related content on “Art,” then another prompt would pull in a bit from “Health.”

Then the even bigger question is: can these various methods be stacked on top of each other, so that you are not forced to choose sociocultural or epistemological separately, but the AI could look at both at once? Probably so, but would a tool to create such a lesson be too complex for most people to practically utilize?

![]() Of course, something like this is ripe for bias, so that would have to be kept in mind at all stages. I am not sure exactly how to counteract that, but hopefully if we try to build more options into the system for the learner to choose from, this will start dealing with and exposing that. We would also have to be careful to not turn this into some kind of surveillance system to watch learners’ every move. Many AI tools are very unclear about what they do with your data. If students have to worry about data being misused by the very tool that is supposed to help them, that will cause stress that is detrimental to learning. So in order for something like this to work, openness and transparency about what is happening – as well as giving learners control over their data – will be key to building a system that is actually usable (trusted) by learners.

Of course, something like this is ripe for bias, so that would have to be kept in mind at all stages. I am not sure exactly how to counteract that, but hopefully if we try to build more options into the system for the learner to choose from, this will start dealing with and exposing that. We would also have to be careful to not turn this into some kind of surveillance system to watch learners’ every move. Many AI tools are very unclear about what they do with your data. If students have to worry about data being misused by the very tool that is supposed to help them, that will cause stress that is detrimental to learning. So in order for something like this to work, openness and transparency about what is happening – as well as giving learners control over their data – will be key to building a system that is actually usable (trusted) by learners.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.