If you pay attention to all of the hype and criticism of AI – well, you are super human. But if you try to get a good sampling of what is actually out there, you probably noticed that there are growing concerns (and even some surprising abandonments) of AI. This is just part of what always happens with Ed-Tech trends – I won’t get into various hype models or claims of “it is different this time.” Trying to prove that a trend is “different this time” is actually just part of regular trend cycle anyways.

But like all trends before it, AI is quickly approaching a crossroads that all trends faced. This crossroads really has nothing to do with which way the usage numbers are going or who can prove what. Like MOOCs, Second Life, Google Wave, and other trends before it – AI is seeing a growing criticism movement that has made many people doubt its future. Where will AI go once it does hit this crossroad? Well, only time will tell – but there are three general possibilities.

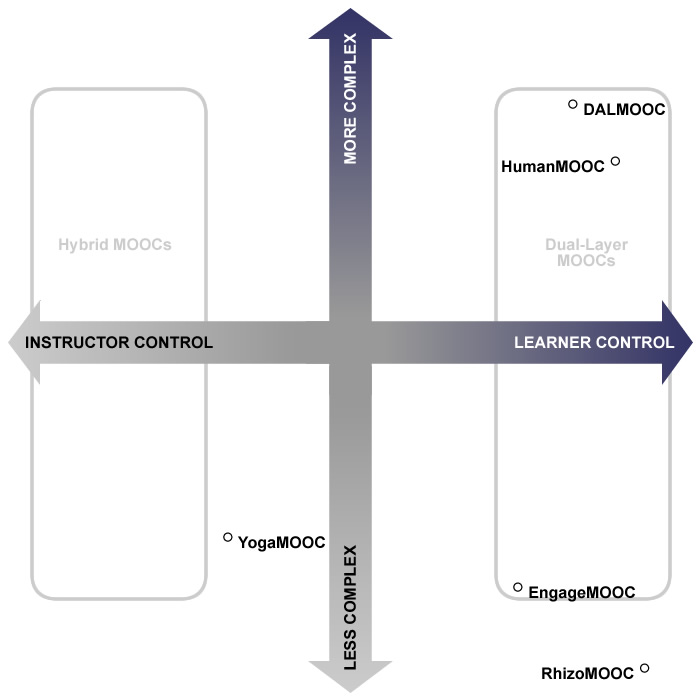

The first option is to follow the MOOC path – a slight fall from popularity (even though many numbers didn’t ever show a decrease in usage) that results in a soft landing as a background tool used by many – but far from the popular trend that gets all of the grant money. Companies like edX and Coursera saw the dwindling MOOC hype coupled with rising criticism, They were able to spin off something that is still used by millions every day – but essentially is not driving really much of anything in education anymore. Their companies are there, they are growing – but most people don’t pay much attention to them really.

The second option is to follow the Second Life path of virtual worlds – a pretty hard fall from grace, with a pretty hard landing… but one they still survived and were able to keep going (to this day). Will VR revive virtual worlds? Probably not – but many will try. This option means the trend is kind of still there, but few seem to notice or care any more.

The third option is the Google Wave route – the company just ignore the signs and keep going full speed until suddenly it all falls apart one day. Go out in a whimper of not-too much glory… suddenly.

Where will AI fall? Its hard to say really. My guess is that it will be somewhere between option one and two, but closer to option one. There are some places where AI is useful – but no where near as many places as the AI enthusiasts think it is. Like MOOCs, I think the numbers will still grow despite people moving on to the next “innovative trend” – as people always do. But there is enough momentum to avoid option two, while just enough caution and critics out there to avoid option three. But I could be wrong.

How do I know this is happening with AI? Well, you really can’t know for sure – but it has happened with every educational technology trend. Even the ones that barely became a trend like learning analytics. Some of it just comes from paying attention to Twitter or whatever its called now. Even though that is dying as well. Listening to what people are saying – both good and bad – is something that you won’t get from news releases or hype.

But still, you can look at publications, blogs, and even the news to see that the criticism of AI is growing. People are noticing the problems with racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, etc in the outputs. People are noticing that the quality of output isn’t as great as some claim once you move past the simplistic examples utilized in demos and start using it in real life. Yes, people are getting harmed and killed by it (not just referring to the Tesla self-driving AI running over people here, but that one should have been enough). Companies are starting to turn against it – some are doing so quietly after disappointing results, just so they can avoid public embarrassment. Students are starting to talk about starting lawsuits against schools that use AI – they were promised a real-world education and don’t feel AI generated content (especially case studies) counts as “real world.” Even when the output is reviewed by real humans… they do have a point.

Of course, there is always the promise that AI will get better – and I guess, it is true that the weird third hands and mystery body parts that keep appearing in AI art are becoming mostly photo realistic. Never mind that they just can’t seem to correct the core problem of extra body parts despite decades of “improvements” in image generation. Content generation still makes the same mistakes it did decades ago with getting the idea correct, but at least it doesn’t make typos any more I guess?

A major part of the problem is that AI developers are often not connected to the real world contexts their tools need to be used in. When you see headlines about “AI is better that humans at creativity” or “AI just passed this course,” you are usually assaulted by a head-desk inducing barrage of how AI developers misunderstanding core concepts of education. Courses were designed for humans without “photographic memory” as well as those that are not imbued with The Flash-level speed to search through the entire Internet. AI by definition is cheating at any course or test it takes because it has instant access to every bit of information it has been trained on. Saying it ever “passed” a test or course is silliness on the level of academic fraud.

I could also go off on the “tests” they use to see if AI is “creative.” These tests are complete misunderstandings of what creativity is or how you use it. It is kind of true that there is nothing new under the sun, so human tests of creativity are actually testing an individual’s novelty at coming up with a solution that they have never seen before for the rope, box, pencil, and candle they give them for the test. AI by definition can never pass a creativity test because it is just not able to come up with novel ideas when it has seen them all and can instantly pull them up.

Don’t listen to anyone that claims AI can “pass” a test or “do better than humans” at a test or course – that is a fraudulent claim disconnect from reality.

There is also the issue of OpenAI/ChatGPT running out of funding pretty soon. Maybe they will get more, but they also might not. It is actually a slight possible that one day ChatGPT just won’t be there (and suddenly all kinds of AI services secretly running ChatGPT in the background will also be exposed). If I had a job that depended on ChatGPT completely – I would begin to look elsewhere possibly.

Even Instructional Design is showing some concerning signs that AI is fast approaching this inevitable crossroad. So many demonstrations of “AI in ID” just come down to using AI to create a basic level course in AI. We are told that this can reduce creation of a draft of a course to something wildly short like 36 hours.

However – when you are talking about Intro to Chemistry classes, or Economics 101 type courses – there are already thousands of those classes out there. Most new or adjunct instructors are given an existing course that they have to teach. Even if not – why take 36 hours to create a draft when you can usually copy an existing course shell from the publisher in a minute or less? Most IDs know that the bulk of design work comes from revising the first draft. Plus, most instructors reject pre-designed templates because they want to customize it the way they want. If they have been rejecting pre-designed textbook resource materials for decades, they aren’t going to accept AI generated materials. And I haven’t even touched on the fact that so much ID work is on more specific courses that don’t have a ton of material out there because they are so specific. AI won’t be able to do much for those because they don’t have near as much material to train on.

And don’t get me started on all of those “correct the AI output” assignments. Fields that have never had a “correct the text” assignments are suddenly utilizing these… for what? Their field doesn’t even need people to correct text now. It’s just a way to shoehorn new tech into courses to look “innovative.” If your field actually will need to correct AI output, then you are one of the few that need to be training people to do this. Most fields will not.

All of this technology-first focus just emphasizes the problems that have existed for decades with technology-worship. Wouldn’t things like a “Blog-First University” or a “Google-First Hospital” have sounded ridiculous back when those tools were trends? Putting any technology first generally is a bad idea no matter what that technology is.

But ultimately, the problem here is not the technology itself. AI (for the most part) just sits on computers somewhere until someone tells it what to do. Even those AI projects that are coming up with their own usage where first told to do that by someone. The problem – especially in education – is just who that someone is. Because in the world of education, it will be the same people it always has been making the calls.

The same people that have been gatekeeping and cannibalizing and surveilling education for decades will be the ones to call the shots with what we do with AI in schools. They will still cause the same problems with AI – only faster and more accurate I guess. The same inequalities will be perpetrated. It will more of the same, probably just intensified and sped up. I mean, a well-worshipped grant foundation researched their own impact and found no positive impact, but the education world just yawned and kept their hands extended for more of that sweet, sweet grant funding.

![]() As many problems as there are with AI itself, even if someone figures out how to fix them… the people in charge will still continue to cause the same problems they always have. And there are some good people working on many of the problems with AI. Unfortunately, they aren’t the ones that get to make the call as to how AI is utilized in education. It will be the same people that hold the power now, causing the same problems they always have. But too few care as long as they get their funding.

As many problems as there are with AI itself, even if someone figures out how to fix them… the people in charge will still continue to cause the same problems they always have. And there are some good people working on many of the problems with AI. Unfortunately, they aren’t the ones that get to make the call as to how AI is utilized in education. It will be the same people that hold the power now, causing the same problems they always have. But too few care as long as they get their funding.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.