So it started off innocent enough, with a Tweet about concerns regarding the popular QM rubric for course review:

https://twitter.com/steph_moore/status/1291758870394802177

Different people have voiced concerns with the rubric through the years… usually not saying that it is all bad or anything, but just noting that it presents itself as a “one rubric for all classes” that actually seems to show a bias for instructor-centered courses with pre-determined content and activities. Now, this describes many good classes – don’t get me wrong. But there are other design methodologies and learning theories that produce excellent courses as well.

The responses from the QM defenders to the tweet above (and those like me that agreed with it) were about many things that no one was questioning: how it is driven by research (we know, we have done the research as well), lots of people have worked for decades on it (obviously, but we have worked in the field for decades as well; plus many really bad surveillance tools can say the same, so be careful there), QM is not meant to be used this way (even though we are going by what the rubric says), it is the institution’s fault (we know, but I will address this), people who criticize QM don’t know that much about it (I earned my Applying the QM Rubric (APPQMR) certificate on October 28, 2019 – so if don’t understand, then whose fault is that? :) ), and so on.

Now technically most of us weren’t “criticizing” QM as much as discussing it’s limitations. Rubrics are technology tools, and in educational technology are told to not look at tools as the one savior of education. We are supposed to acknowledge their uses, limitations, and problems. But every time someone wants to discuss the limitations of QM, we get met with a wall of responses bent on proving there are no limitations to QM.

The most common response is that QM does not suggest how instructors teach, what they teach, or what materials they use to teach. It is only about online course design and not teaching. True enough, but in online learning, there isn’t such a clear line between design and teaching. What you design has an effect on what is taught. In fact, many online instructors don’t even call what they do “teaching” in a traditional sense, but prefer to use words like “delivery” or “facilitate” in place of “teaching.” Others will say things like “your instructional design is your teaching.” All of those statements are problematic to some degree, but the point is that your design and teaching are intricately linked in online education.

But isn’t the whole selling point of QM the fact that it improves your course design? How do you improve the design without determining what materials work well or not so well? How do you improve a course without improving assignments, discussions, and other aspect of “what” you teach? How do you improve a course without changing structural options like alignment and objectives – the things that make up “how” you teach?

The truth is, General Standards 3 (Assessment and Measurement), 4 (Instructional Materials), and 5 (Learning Activities and Learner Interaction) of the QM rubric do affect what you teach and what materials you use. They might not tell you to “choose this specific textbook,” but they do grade any textbook, content, activity, or assessment based on certain criteria (which is often a good thing when bad materials are being used). But those three General Standards – along with General Standard 2 (Learning Objectives (Competencies)) – also affect how you teach. Which, again, can be a good thing when bad ideas are utilized (although the lack of critical pedagogy and abolitionist education in QM still falls short of what I would consider quality for all learners). So we should recognize that QM does affect the “what” and “how” of online course design, which is the guide for the “what” and “how” of online teaching. That is the whole selling point, and it would be useless as a rubric if it didn’t help improve the course to do this.

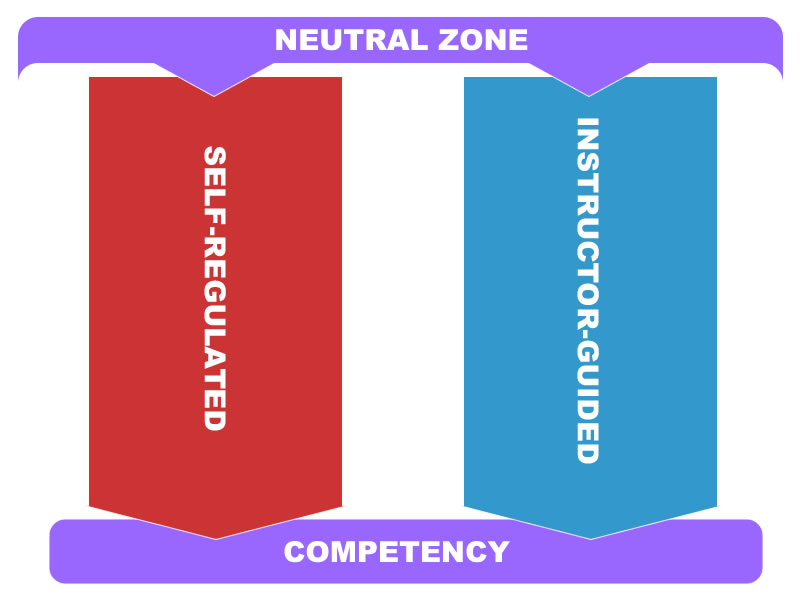

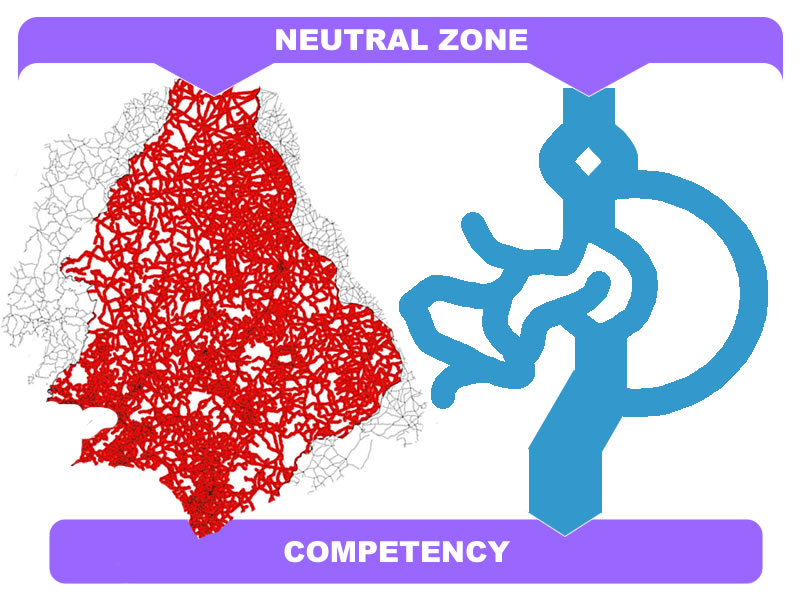

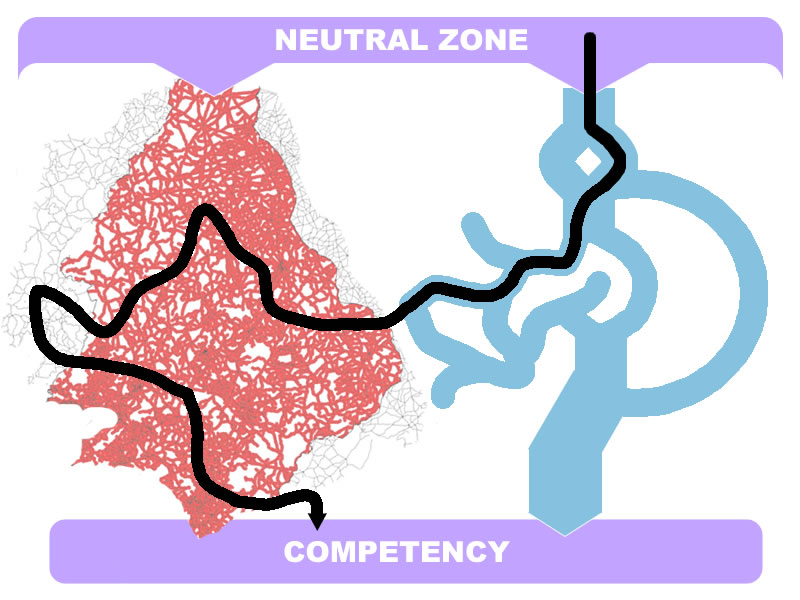

So, yes, specific QM review standards require certain specific course structures that do dictate how the course is taught. The QM rubric is biased towards certain structures and design methodologies. If you are wanting to teach a course that works within that structure (and there are many, many courses that do), QM will be a good tool to help you with that structure. However, if you start getting into other structures of ungrading, heutagogy / self-determined learning, aboriginal pedagogy, etc, you start losing points fast.

This is has kind of been my point all along. Much of the push back against that point dives into other important (but not related to the point) issues such as accreditation, burnout, and alignment. Sometimes people got so insulting insulting that I had to leave the conversation and temporarily block and shut it out of my timeline.

QM evangelists are incredibly enthusiastic about their rubric. As an instructional designer, I am taught to question everything – even the things I like. Definitely not a good combination for conversation it seems.

But I want to go back and elaborate on the two points that I tried to stick to all along.

The first point was a response to how some implied that QM is without bias… that it is designed for all courses, and because of this, if some institutions end up using it as a template to force compliance, that is their bias and not QM’s fault. And I get it – when you create something and people misuse it (which no one is denying happens), it can be frustrating to feel like you are being blamed for other’s misuse. But I think if we take a close look at how QM is not unbiased, and how there are politics and bias built into every choice they made, we can see how that has the effect of influencing how it is misused at institutions.

QM is a system based on standardization that was created by specific choices that were chosen through bias, in a method that biases it towards instructor-centered standardized implementation by institutional systems that are known to prefer standardization.

I know that sounds like a criticism, but there are a couple of things to first point out:

- Bias is not automatically good or bad. Some of the bias in QM I agree with on different levels. Bias is a personal opinion or organizational position, therefore choosing one option over another always brings in bias. There is no such thing as bias-free tech design.

- The rubric in QM is Ed-Tech. All rubrics are Ed-Tech. That makes QM an organization that sells Ed-Tech, or an Ed-Tech organization. This is not saying that Ed-Tech is their “focus” or anything like that.

Most people understand how that QM was designed to be flexible. But even those QM design choices had bias in them. All design choices have bias, politics, and context. And when the choices of an entity such as QM are packaged up and sold to an institution, they are not being sold to a blank slate with no context. The interaction of the two aspects causes very predictable results, regardless of what the intent was.

For example, the QM rubric adds up to 100 points. That was a bias point right there. Why 100? Well, we are all used to it, so it makes it easy to understand. But it also connects to a standardized system that we were mostly all a part of growing up, one that didn’t have a lot of flexibility. If we wanted to score higher, we had to conform. When people see a rubric that adds up to 100, that is what many think of first. Choosing a point total that connects with pre-existing systems that also utilize that highest score is a choice that brings in all of the bias, politics, and assumptions that are typically associated with that number elsewhere.

Also, the ideal minimum score is 85. Again, that is biased choice. Why not 82, or 91, or 77? Because 85 is the beginning of “just above average” of the usual “just above average score” (a “B”) that many are used to. Again, this connects to a standardized system we are used to, and reminds people of the scores they got in grade school and college.

In fact, even using points in general, instead of check marks or something else, was another choice that QM made that is also a biased choice. People see points and they think of how those need to add up to the highest number. This mindset affects people even when they get a good number: think of how many students get an 88 and try to find ways to bump it up to a 90. This is another systemic issue that many people equate to “follow the rules, get the most points.”

Then, when you look at how long some of the explanations of the QM standards are, again that was a choice and it had bias. But when combined with an institutional system that keeps its faculty and staff very busy, it creates a desire to move through the long, complicated system as fast as possible to just get it done. This creates people that game the system, and one of the best ways to hack a complex process that repeats itself each course is to create a template and fill it out.

While templates can be a helpful starting place for many (but not everyone), institutional tendency is to do what institutions do: turn templates into standards for all.

This is all predictable human behavior that QM really should consider when creating its rubric. I see it in my students all the time – even though I tell them that there is flexibility to be creative and do things their way, most of them still come back to mimicking the example and giving me a standardized project.

You can see it all up and down the QM rubric – each point on the rubric is a biased choice. Which is not to say that they are all bad, it’s just that they are not neutral (or even free from political choices). Just some specific examples:

- General Standard 3.1 is based on “measure the achievement” – which is great in many classes, but there are many forms of ungrading and heutagogy and other concepts that don’t measure achievement. Some forms of grading don’t measure achievement, either.

- General Standard 3.2 refers to a grading policy that doesn’t work in all design methodologies. In theory, you could make your grading policy about ungrading, but in reality I have heard that this approach rarely passes this standard.

- General Standard 3.3 is based on “criteria,” which is a popular paradigm for grading, but not compatible with all of them.

- General Standard 3.4 is hard to grade at all in self-determined learning when the students themselves have to come up with their own assessments (and yes, I did have a class like that when I was a sophomore in college – at a community college, actually). Well, I say hard – you really can’t depending on how far you dive into self-determined learning.

- General Standard 3.5 seems like it would fit a self-determined heutagogical framework nicely… in theory. In reality, its hard to get any points here because of the reasons covered in 3.4

Again, the point being that it is harder for some approaches like heutagogy, ungrading, and connectivism to pass. If I had time and space, I would probably need to go into what all of those concepts really mean. But please keep in mind that these methods are not “design as you go” or “failing to plan.” These are all well-researched concepts that don’t always have content, assessment, activities, and objectives in a traditional sense.

Many of the problems still come back to the combination of a graded rubric being utilized by a large institutional system. A heutagogical course might pass the QM rubric with, say, an 87 – but the institution is going to look at it as a worse course than a traditional instructivist course that scores a 98. And we all know that institutional interest in the form of support, budgets, praise, awards, etc will go towards the courses that they deem as “better” – this is all a predictable outcome from choosing to use a 100 point scale.

There are many other aspects to consider, and this post is getting too long. A couple more rabbit trails to consider:

[tweet 1299002302137802753 hide_thread=’true’]

And I really don’t mean this to be cheeky, but the entire idea of a “review standard” is at odds with ungrading, in my view. Different students learn in different ways in different contexts at different times and with different teachers.

— Jesse Stommel (@Jessifer) August 27, 2020

![]() So, yes, I do realize that QM has helped in many places where resources for training and instructional designers are low. But QM is a rubric, and rubrics always fall apart the more you try to make them become a one-size-fits-all solution. Instead of trying to expand the one Higher Ed QM rubric to fit all kinds of design methodologies, I think it might be better to look at what kind of classes it doesn’t work with and move to create a part of the QM process that identifies those courses and moves them on to another system.

So, yes, I do realize that QM has helped in many places where resources for training and instructional designers are low. But QM is a rubric, and rubrics always fall apart the more you try to make them become a one-size-fits-all solution. Instead of trying to expand the one Higher Ed QM rubric to fit all kinds of design methodologies, I think it might be better to look at what kind of classes it doesn’t work with and move to create a part of the QM process that identifies those courses and moves them on to another system.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.