It all started off simply enough. Someone saw a usage of analytics that they didn’t like, and thought they should speak up and make sure that this didn’t cross over into Learning Analytics:

The responses of “Learning Analytics is not surveillance” came pretty quickly after that:

[tweet 1187857679206637568 hide_thread=’true’]

But some disagreed with the idea, feeling they are very, very similar:

[tweet https://twitter.com/Autumm/status/1188110779616288775 hide_thread=’true’]

(a couple of protected accounts that I can’t really embed here did come out and directly say they see Learning Analytics and Learning Surveillance as the same thing)

I decided to jump in the conversation and ask some questions about the difference between the two, and see if anyone could given definitions of the two that explained their difference, or perhaps prove they are they same.

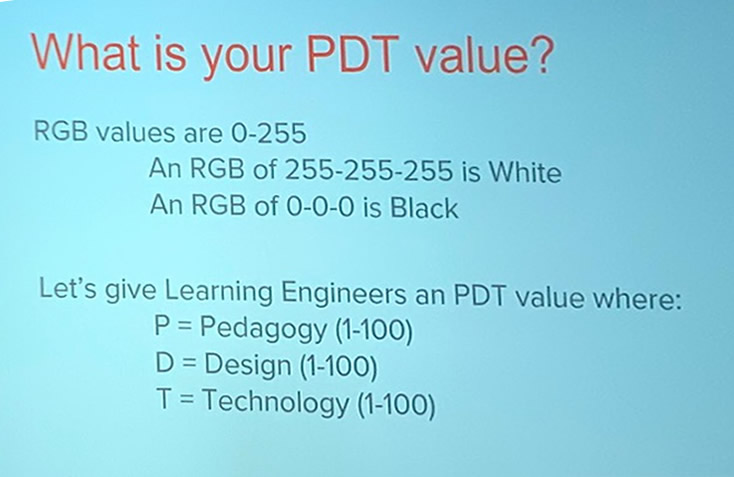

My main point was that there is a lot of overlap between the two ideas. Both Learning Analytics and Learner Surveillance collect a lot of student data (grades, attendance, click stream, demographics, etc). If you look at the dictionary definition of surveillance (“close watch kept over someone or something (as by a detective)”), the overlap between the two only grows. Both rely on the collection of data to detect, keep watch, and predict future outcomes, all under the banner of being about the learning itself. Both Learning Analytics researchers and Learning Surveillance companies claim they do their work for the greater good of helping us to understand and optimize learning itself and/or the environments we learn in. The reality is that all surveillance (learning or otherwise) is now based on data that has been analyzed. If we don’t define the difference between Learning Analytics and Learner Surveillance, then the surveillance companies will continue to do what they want with Learning Analytics. Just saying “they are not the same” or “they are the same” without providing quantitative definitions of how they are or are not the same is not enough.

It seems that the questions that were raised in replies to my thread showcase how there is not a clear consensus on many aspects of this discussion. Some of the questions raised that need to be acknowledged and hashed out include:

- What counts as data, especially throughout the history of education?

- What exactly counts as surveillance and what doesn’t?

- Is surveillance an inherently evil, oppressive thing; a neutral force that completely depends on the answer to other questions here; or a benign overall positive force in society? Who defines this?

- Does the purpose of data collection (which is driven by who has access to it and who owns it) determine it’s category (analytics or surveillance)?

- Does the intent of those collecting data determine it’s category?

- Does consent change the nature of what is happening?

- Is Learning Analytics the same, similar in some ways but not others, or totally different than Learning Surveillance?

- What do we mean by the word “learning” in Learning Analytics?

- Are the benefits of Learning Analytics clear? Who gets to determine what is a “benefit” or not, or what counts as “clear”?

I am sure there are many other questions (feel free to add in the comments). But lets dig into each of these in turn.

The Historical Usage of Data in Education

There have been many books and papers written on the topic of what data is, but I got the sense that most people recognize that data has been used in education for a long time. Many took issue with equating Learning Analytics with collecting one data point:

This is a good point. Examining one data factor falls well short of any Learning Analytics goal I have ever read. Seeing that certain data points such as grades, feedback, attendance, etc have always been used in education, at what point or level does the historically typical analysis of information about learners become big data or Learning Analytics? If someone is just looking at one point of data, or they are looking at a factor related to the educational experience but not at learning itself, do we count it as “Learning Analytics”? If not, at what point does statistical information cross the line into becoming data that can be analyzed? How many different streams of data does one have to analyze before it becomes learning analytics? How close does the data have to be to the actual educational process to be considered Learning Analytics (or something else)? Does Learning Analytics even really ever look at actual learning? (more on that last one later)

What is Surveillance Anyways?

It seems there is a range of opinions on this, from surveillance meaning only specific methods of governmental oppression, to the very broad general definition in various dictionaries. Some would say that if you make your data collection research (collected in aggregate, de-identified, and protected by researchers), then it is not surveillance. Others say that analytics requires surveillance. Others take those ideas in a different direction:

https://twitter.com/gsiemens/status/1188112736934420487

I don’t know if I would ever go that far (and if you know George, this is not his definitive statement on the issue. I think.), or if I even feel the dictionary definition is the most helpful in this case. But you also can’t disagree with Miriam-Webster, right? Still, there are some bigger questions about what exactly is the line between surveillance and other concepts:

[tweet 1188147893246410752 hide_thread=’true’]

Oversight, supervision, corporate interest, institutional control, etc… don’t they all affect where we draw the line between analytics and surveillance (if we even do)? Or even deeper still….

Is All Surveillance Evil?

It seems there is an assumption that all surveillance is evil in some corners. Some even equate it with oppression and governmental control. However, if that is what everyone thinks of the idea, then why do grocery stores and hotels and other businesses blatantly post signs that say “Surveillance in Progress“? My guess is that this shows there are a lot of people that don’t see it as automatically bad, and even more that don’t care that it is happening. Or do they really not care, or just think there is nothing they can do about it? Either way, these signs would be a PR disaster for the companies if there was consensus that all surveillance is evil. Then again, I’m not so sure many would be so accepting of surveillance if we really knew all of the risks.

However, many do see surveillance as evil. Or at least, something that has gone too far and needs to stop:

But taking attendance and tracking bathroom breaks for points are two different things, right? So does that mean that…

Does the Purpose of Data Collection Change Anything?

Many people pointed out that the purpose for why data was collected would change whether we label the actions “Learning Analytics” or “Learning Surveillance.” Of course, the purpose of data collection is also driven by who has access to the data, who owns it, and what they need the data for (control? make money? help students? All of the above?). There is sometimes this assumption that research always falls into the “good” category, but that would ignore the history of why we have IRBs in the first place. Research can still cause harm even with the best of intentions (and not everyone has the best of intentions). This is the foundation of why we do the whole IRB thing, and that is not a perfect system. But the bigger view is that research is all about detective work, watching others closely to see what is going on, etc. Bringing the whole “purpose” angle into the debate will just cause the definition of Learning Analytics to move closer to the dictionary definition of surveillance.

On the other hand, a properly executed research project does keep the data in the hands of the researchers – and not in the hands of a company that wants to monetize the data analysis. Does the presence of a money making purpose cross the line from analytics to surveillance? Maybe in the minds of some, but this too causes confusion in that some analytics researchers are making sell-able products from their research. They may not be monetizing the product itself, but they may sell their services to help people use the tools. And its not wrong to sell your expertise on something you created. But many see a blurry line there. Purpose does have an effect, but not always a clear cut or easy to define one. Plus, some would point out that purpose is not as important as your intentions…

The Road to Surveillance is Paved With Good Intentions

Closely related to purpose is intent – both of which probably influence each other in most cases. While some may look at this as a clear-cut issue of “good” intentions versus “bad” intentions, I don’t personally see that as the reality of how people view themselves. Most companies view themselves as doing a good thing (even if they have to justify some questionable decisions). Most researchers see themselves as doing a good thing with their research. But we have IRBs and government regulation for a reason. We still have to check the intentions of researchers and businesses all the time.

But even beyond that – who gets to determine which intentions are good and which aren’t? Who gets to says what intentions still cause harm and which ones don’t? The people with the intentions, or the people affected by the intentions? What if there are different views among those that are affected? Do analytics researchers or surveillance companies get to choose who they listen to? Or if they listen at all? And are the lines between “harmful good intention” and “positive results of intention” even that clear? Where do we draw the line between harm and okay?

Some would say that the best way to deal with possibly harmful good intentions is to get consent….

Does the Line Between Analytics and Surveillance Change Due to Consent?

Some say one of the lines between Learning Surveillance and Learning Analytics is created by consent. Learning Analytics is research, and ethical research can not happen without consent.

[tweet 1188124784942551040 hide_thread=’true’]

Of course, the surveillance companies would come back and point to User Agreements and Terms of Service. So they are okay with consent, right?

Well, no. Who really reads the Terms of Service, anyways? Besides, they typically don’t clearly spell out what they do with your data anyways, right?

While this is often true, we see the same problem in research. We often don’t spell out the full picture for research participants, and then don’t bother to check to see if they really read the Informed Consent document or not. To be honest, consent in research as well as agreement with Terms of Service is more of a rote activity than a true consent process. We are really fooling ourselves if we think these processes count as consent. They really count more as a legal “covering the buttocks” than anything else.

Of course, many would point out that Learning Surveillance is often decided at the admin level and forced on all students as a condition of participating in the institution. And sadly, this is often the case. Since research is always (supposed to be) voluntary, there is some benefit to Informed Consent over Terms of Service, even if both are imperfect. But after all of this…

So, For Real, What is the Difference Between Analytics and Surveillance?

I think some people see the difference as:

Learning Analytics: informed consent, not monetized, intending to help education/learners, based on multiple data points that have been de-identified and aggregated.

Learning Surveillance: minimal consent sought from end users (forced by admin even), monetized, intending to control learners, typically focused on fewer data points that can identify individuals in different ways.

…or, something like that. But as I have explored above, this is not always the clear-cut case. Learning Analytics is sometimes monetized. Learning Surveillance often sells itself as helping learners more than controlling. De-identified data can be re-identified easier and easier as technology advances. Learning Surveillance can utilize a lot of data points, while some Learning Analytics studies focus in on a very small number. Both Learning Analytics and Learning Surveillance have consent systems that are full of problems. Learning Analytics can be used to control rather than help. And so on.

And we haven’t even touched on the problem of Learning Analytics not really even analyzing actual “learning” itself…

Learning Analytics or Click Stream Analytics?

Much of the criticism of Learning Surveillance focuses on how these tools and companies seek to monitor and control learning environments (usually online), while having very little effect on the actual learning process. A fair point, one that most Surveillance companies try to downplay with research of their own. That’s not really an admission of guilt as much as it is just the way the Ed-Tech game goes: any company that wants to sell a product to any school is going to have to convince the people with the money that there is a positive affect on learning. Some how.

But does Learning Analytics actually look at learning itself?

[tweet 1188243487071834112 hide_thread=’true’]

So while Learning Analytics does often get much closer to examining actual learning than Learning Surveillance usually does, it is generally still pretty far away. But so is most of educational research, to be honest. It is not possible yet to tap into brains and observe actual learning in the brain. And a growing number of Learning Analytics papers are taking into account the fact that they are looking at artifacts or traces of learning activities, not the learning activities themselves or the actual learning process.

However, the distinction that “Analytics is looking at learning itself” and “Surveillance is looking at factors outside of learning” still comes apart to some degree when you look at what is really happening. Both of them are examining external traces or evidence of internal processes. This leaves us with the idea that there has to be a clear benefit to one or other if there is a true difference between the two….

What is Clear and What is a Benefit Anyways?

Through the years, I have noticed that many say that the benefits of analytics and/or surveillance are clear. The problem is, who gets to say they are clear, or that they are beneficial? All kinds of biases have been found in data and algorithms. If you are a white male, there are fewer risks of bias against you… so you may see the benefits as clear. To those that see a long history of bias being programmed into the systems… not so much. Is it really a “benefit” if it leaves out large parts of society because a bias was hard-coded into the system?

Where some people see benefits of analytics, other see reports tailored for upper level admin that tells them what we already know from research. Having participated in a few Learning Analytics research projects myself, I know that it takes a lot of digging to find results, and then an even longer time to explain to others what is there. And then, if you create some usable tool out of it, how long does it take to train people to use those results in “user-friendly” dashboards? Obviously, in academia we don’t have a problem with complex processes in and of themselves. But we should also be reluctant to call them “clear” if they are time-consuming to discover, understand, communicate, and make useful for others.

Then, on top of all of this, what we have had so far is a bunch of instructors, admins, and researchers arguing over whether analytics is surveillance, and if either one of them are okay or not. Do the students get a say? When are we going to take the time to see if students clearly understand what all this is about (and then clearly explain it to them if they don’t), and then see what they have to say? Some already understand the situation very well, but we need to get to place where most understand it fairly well, and then include their voice in the discussion.

So Back to the Question: How Do You Define These Two?

Like many have stated, analytics and surveillance have existed for a long time, especially in formal educational settings:

If you really think about it, Instructivism has technically been based on surveillance and analysis all along. This has kind of been baked into educational systems from the beginning. We can’t directly measure learning in the brain, so education has traditionally chosen to keep close watch over students while searching for evidence that they learned something (usually through tests, papers, etc). Our online tools have just replicated instructor-centered structures for the most part, bringing along the data analysis and user surveillance that those structures were known for before the digital era. Referring to teachers as “learning detectives” is an obscure trope, but one that I have heard from time to time.

(Of course, there are those that choose other ways of looking at education, utilizing various methods to support learner agency. This is outside the focus of this rambling article. But it is also the main focus of the concepts I research, even when digging into data analytics.)

So if you are digging through large data sets of past student work and activity like a detective, in order to find ways to improve educational environments or the learning process…. am I describing Learning Analytics, or Learning Surveillance?

Yes, I intentionally choose a sentence that could easily describe both on purpose.

To be honest, I think if we pull back too far and compare any type of data analysis in learning with any form of student surveillance in learning, there won’t be much difference between the two terms. And some people that only work occasionally with either one will probably be okay with that.

I think we need to start looking at Learning Analytics (with capital L-A) vs. analytics (little a), and Learning Surveillance (capital L-S) vs. surveillance (little s). This way, you can look at the more formal work of both fields, as well as general practices of the general ideas. For example, you can look at the problems with surveillance in both Learning Analytics as well as in Learning Surveillance.

However, if I was really pressed, I would say that Learning Analytics (with capital L-A) seeks to understand what is happening in the learning process, in a way that utilizes surveillance (little s) of interface processes, regardless of monetary goals of those analyzing the data. Learning Surveillance (capital L-S) seeks to create systems that control aspects of the learning environment in a way that monetizes the surveillance process itself, utilizing analytics (little a) from learning activities as a primary source of information.

You may look at my poor attempt at definitions and feel that I am describing them as the exact same thing. You may look at my definitions and see them as describing two totally different ideas. Maybe the main true difference between the two is in the eye of the beholder.

You may look at my poor attempt at definitions and feel that I am describing them as the exact same thing. You may look at my definitions and see them as describing two totally different ideas. Maybe the main true difference between the two is in the eye of the beholder.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.

![]() Of course, I like the whole book, so it was hard to pick just a few chapters, but those are the ones that would probably help those getting online quickly. When you get more caught up, I would also suggest the Basic Philosophies chapter as one to help guide you think through many underlying aspects to teaching online.

Of course, I like the whole book, so it was hard to pick just a few chapters, but those are the ones that would probably help those getting online quickly. When you get more caught up, I would also suggest the Basic Philosophies chapter as one to help guide you think through many underlying aspects to teaching online.