So to continue the examination of the multiple pathways MOOC (aka “dual-layer”), I want to pull back a minute and look at the overall flow of the course from a different (but familiar) perspective.

One of the ways I think we are falling flat in MOOCs (and to be honest, all forms of courses) is in the process of introducing the course and maintaining an overall vision. A colleague of mine often says “without vision, the people perish!” What this basically means if that people don’t have a good reason to get pumped up about what they are doing, they give up. Another way of looking at this is: “[insert your topic here]: So What?!?!”

Introductory sections and goals are good components to have, but they aren’t enough to bring vision to all learners (some will be self-motivated, of course). In traditional courses, the “So what?” can easily be answered with “I paid for it, its required, it helps my degree plan, so good enough!” While that is not the best vision, it usually fills the gap. So a bit of problem there, but with a stop gap. But in open classes? People need a better answer to “so what?” than that (because they can drop out with no loss) or even any answer, period.

And not because they aren’t necessarily interested or motivated. They just need some fuel to keep their self-motivation fires burning when the pressures of life press in to the time needed for self-selected course.

This is the beginning of the process of Heutagogy, which will continue into the next issue to examine.

One of the major criticisms of some college programs is that they are focusing too much on content and not enough on marketable skills. In any technology-related field, this causes problems when that content goes obsolete. For example, computer programming degrees may teach, say, “Intro to PHP” and “Advanced PHP” in the sophomore year – typically with a textbook that is already a few years old. However, three years later when those students graduate, that PHP has gone thorough several new versions, while many companies have moved on to Ruby on Rails. So the learners panic because they realize “I need a class on the new version of PHP and Ruby on Rails! But I am out of college!”

What this does is create a reliance on the instructor as knowledge dispenser and the class as “specific skill set trainer.” What is missing is teaching learners how to learn (aka heutagogy) instead of how to consume content from an expert (instructivism).

At the very beginning, computer programming college degrees should focus on teaching students how to figure out any programming language. Just look at basic concepts, theories, and then several method out there. Because different learners will be, well, different – they will need to figure out if they need Dummies books or online tutorials or to work alone or to follow an expert or whatever it means. Once they have their own process down, the rest of the program should focus on honing these self-directed learning skills by letting learners loose on whatever the language de jour is. But the classes should not be called “Advanced Java” or what ever it may be, but “Solving Advanced Problems Using New Languages” or something like that. Since changing course titles and textbooks is very difficult to accomplish quickly, just make the titlesmore open from the beginning to allow for students to pursue more up-to-date and/or relevant content. Or just go all crazy and allow for more advanced open learning.

Pulling this altogether, I would look at a theoretical flow of content like this (based on data analytics, the current topic of a the multiple pathways MOOC):

1) Give learners vision (and let the vision frame the rest of the class). Have all instructors answer the “Data Analytics: So What?” in a short video of a few minutes. And then I would say just slam the learners into group work. Have all learners answer this question before class even starts:

If someone came up to you on the streets and said “Data Analytics: So What?”, my answer would be:

a) adequate to inspiring

b) some what uncertain to non-existent

Then place all learners into groups of five with about 1-2 A’s and 304 B’s. Let those who are already a bit advanced envision the others.

2) Go through the introduction, but the first major topic should be how to identify and follow the major thought leaders and organization in Data Analytics. Once learners connect with these leaders, they have taken their first step to becoming lifelong learners about Data Analytics rather than short-term consumers of expert knowledge that need to keep coming back to the same expert fountains in order to learn and grow. We often leave this step to the end or scatter it as optional content throughout the material, but I think in today’s society this is not adequate. Start off with learning how to find the updated thought on data analytics and let learners begin to find the new ideas and products from the very beginning of class.

3) Dive into the intro material, but expand it to include teaching the basics of how to do Data Analytics in all situations, scenarios, software environments, etc. Teach learners to know how to learn for themselves what to do, not just follow the steps you provide. In data analytics, that would teach them how to analyze the data in general in any program: extracting data, visualizations, network analysis, regressors, etc. Teach them the basics of how to figure out any data analytics tool they come across.

4) Then dive into real life scenarios, problem-based learning, even student centered learning. I know that at times there will be certain functions that only one program does, so I’m not saying avoid any specific instructions. But think of it this way: portions of the specific instructions you teach your learners will be obsolete when the next version that is released. In other cases, many learners will be at an institution that requires one type of software. If you only taught them to figure out the narrative of data using Tableau, and their institution wants them to use Gephi, they may get stuck. But if they learn in general how to look at the narrative of data and then are allowed to choose the tool they use to accomplish this analysis, they might find the course much more meaningful to them as learners.

Of course, I am oversimplifying this idea and real courses will be a mixture of looking at specific functions that only exist in specific places and alongside overarching ideas that can transcend applications. The overall point I am getting at is to focus your design on teaching your learners how to learn about your topic, with the specific tools and processes as examples and case studies rather than the overall focus itself.

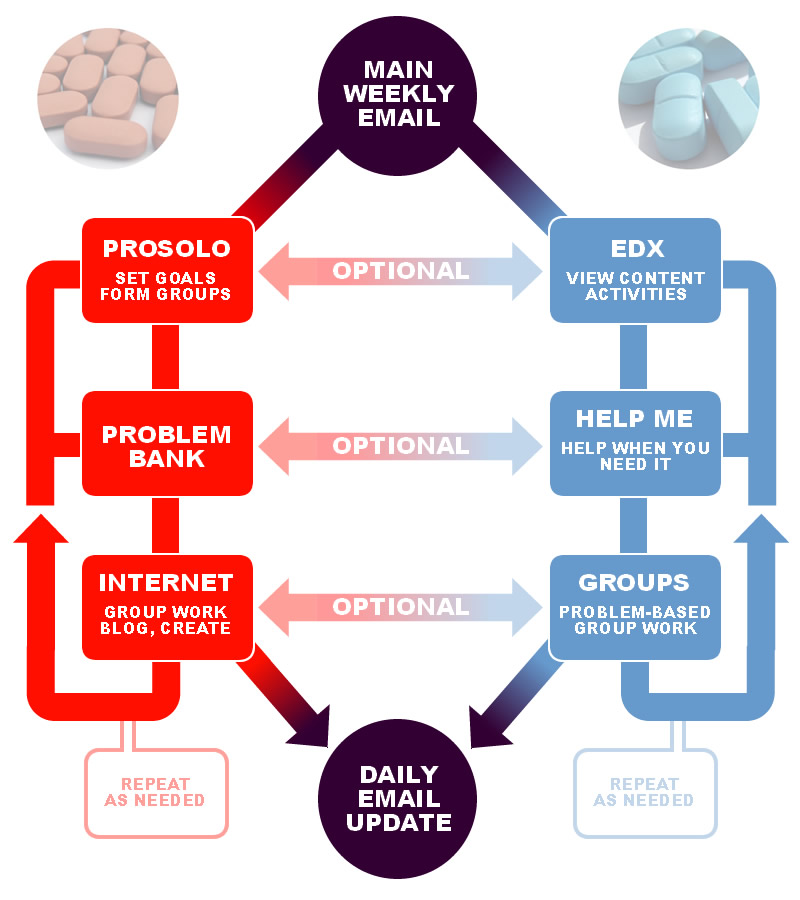

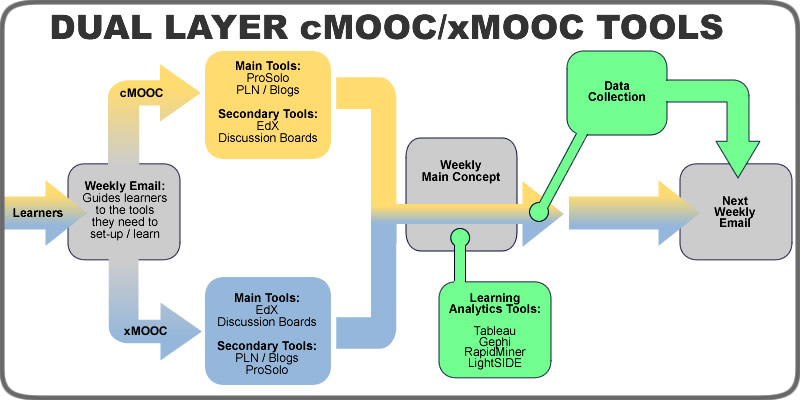

As for how to arrange the tools themselves, I want to look at that idea in more detail in a separate post where we will go on a treasure hunt with Nicholas Cage.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.