Returning again to the design of DALMOOC and more specifically the visual syllabus, I wanted to take a look at the scaffolding decisions that were made. In some ways, this course was a unique challenge because we had to do some true scaffolding that could possible span several different levels of experience, from complete newbie to seasoned expert. This is different than most instances of scaffolding, because typically college curses are really more along the lines of linear constructivism than scaffolding. What I mean is this: for most courses on the college level, you assume that your learners have a prerequisite level of knowledge from either high school or earlier pre-req courses. You aren’t introducing, say, physics for the first time ever – but instead you are building on the Intro to Physics course in order to help students learn how to build rockets and predict launch patterns. So you don’t scaffold as much as take chunks of knowledge and skills and plug them into (linear constructivism) existing knowledge. This is scaffolding at the basic level, but you may or may not go beyond one level of scaffolding.

With DALMOOC, we knew that learning analytics is still new for many, but old news for some that may just want to learn some different tools. Additionally, we were adding in new technology that we knew for a fact that no one had ever used. Throw in that mix an international crowd that won’t all be speaking English and then even add the idea to create a visual syllabus (which few are familiar with). This is a tall order covering a huge range that most courses don’t have to consider.

So where to start? Well, with the first page of the syllabus. It needed to be visual, with minimal text, but clear where to start. A wall of text that basically says “start here” kind of violates a lot of what it needed to be. But if you look at anything from OLC to Quality Matters, most online course evaluation tools recommend having a clear and simple indication of where to start. What is more simple and easy to understand than a basic “1, 2, 3, etc”? I have traveled to Asia and Europe and Africa and even people who don’t know English still understand enough about our number system to know that a web page with those numbers on them would indicate you start with number 1.

Of course, a small number of people felt that this was still too confusing. I’m not sure what to say to that. You are presented with a page that says “Welcome to the Class” and then some big buttons that are labeled 1, 2, 3, etc. I’m not sure what is simpler than that.

Of course, I realize that there are those that really, really need the text because they have been programmed to look for it their whole lives. The buttons were given a rollover effect that gives a more detailed description of what they are leading to. This serves two purposes. One, it gives detailed descriptions that are there when you need them, but aren’t filling the screen and overwhelming people that are completely new. Two, they make you actually do something with the syllabus instead of just passively reading a wall of text. You have to mouse over or click on various items to get more details. This moves you from passive to (slightly) active. This was on purpose to get learners engaging more with the content on the very first page. Additionally, this idea was continued on the other various visuals.

For those that are not new to all of this, links were provided on the upper right hand corner – where they usually are on most websites. We don’t expect people to follow the path laid out for them. In fact, we encouraged learners to skip around and make their own path as needed. And that was also possible from the design.

As expected, there was some push back from a few learners (about 5-10 out of the 6,000 that were active at some point) on the design. The basic feedback was that they didn’t like the roll over effects. They wanted the text to be there without rolling over. This probably tells me that the right decision was made, because that was exactly what the rollover effects were designed to do: make the learner do something instead of passively absorbing text. Of course, there are other ways to accomplish the same goal, so other ideas might be used in the future.

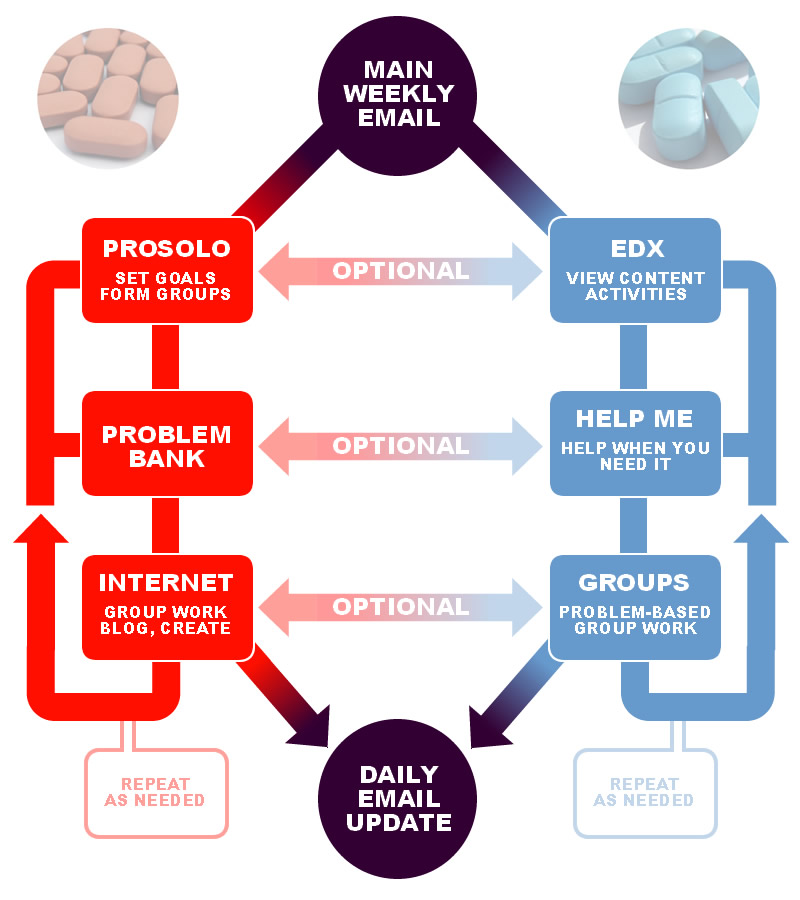

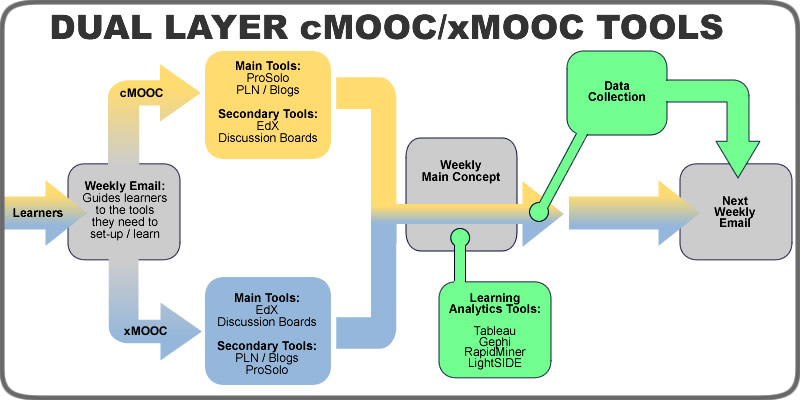

The biggest challenge in describing the structure was how to explain the nature of the dual layer course. Course themes are always helpful, as the many versions of ds106 have proven. Of course, it would have been nice to have enough time to have carried out the theme for the whole class. Many of the problems with understanding the structure can probably be traced to the fact that we were not able to inject this theme throughout the entire course (of course, those problems could also come from the fact that we initially designed the daily email to be the central anchor for the course (and therefore, the place were scaffolding and structure sense-making would happen)). It seems like that aspect fell short. However, I think that a consistent theme that is carried throughout the course as a true sensemaking/guidance tool would alleviate many of these issues. Of course, scaffolding in general is a problematic concept in this dual layer approach, but that will have to be a topic for another blog post.

The theme itself was chosen early as an initial idea that ended up sticking. I think the Matrix “blue pill/red pill” theme was a good place to start, but gets a little murky once people start mixing the two and bringing in their own ideas (which is, of course, what we want). My first idea was actually a table full of play-dough – all kinds of colors just waiting for learners to pick and choose and make into whatever they like. Ultimately, this leaned too much towards my connectivism bias and was probably too unstructured for new learners who wanted instructivism. I think that a mixture of the two ideas might work as a better theme in the future: learners are initially given the choice of blue or red play-dough, but they can choose one or the other or mix together to make their own shade of purple – or bring in their own colors to create what they want.

Of course, some of the more complex ideas that were thrown around earlier, like creating scaffolding out of objectives or dynamic group formation and changing, never made it into the course. Interestingly enough, some learners (around 10-15) asked for various versions of these ideas, so they may bear exploration in the future.

Underlying these design decisions were some different theoretical perspectives that go beyond Connectivism and Instructivism (LTCA Theory, Heutagogy, Metamodernism, etc) that will need to be explored in a future blog post.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.