Grading has been a contentious topic in some circles of education for decades now. Many outside of those circles seem to accept grading as either a good thing at best, or a necessary evil at worst, all the while never questioning if it is possible to not grade in the first place.

For me, I have found grades problematic for a long time. I used to be firmly against them, but years of teaching has changed my status from “against always” to “still not a fan, but it’s complicated.” What exactly has been complicating my views? Talking to students about grades.

I used to teach various undergrad instructional design courses at the University of Texas at Brownsville (before it merged to become UT Rio Grande Valley). We would have many online discussions about all kinds of education topics in these courses. I often found out how much I had framed my progressive / connectivist / critical lens of instructional design through things that looked good to me as a white person (as well as a male) without considering how those stances looked to people of color.

My anti-grading stance was one of these lens.

So I want to try and capture the overarching conversations and issues that were brought to my attention through these conversations with students and many others through the years.

When educators say “grades are bad,” we often offer a “conversational” approach to grading as an alternative. This typically means that instructors should have a dialogue with learners to give them feedback instead of grades, or at least let students come up with their own grade. Of course, this sounds great when you are white (or male) and you will be having this conversation with someone that probably looks a lot like you. But how does this “conversation” sound to an immigrant to this country? What about a first generation college student that is new to the whole system? What about a woman in a field that is typically dominated by men? What about a person of color at a predominately white university? Would they feel comfortable with having their success in the course rely on a conversation with someone that might not realize their own prejudices?

This is an area where we need to put our own anecdotes aside. Sure, students might be comfortable conversing with you… but what about all instructors in your department? All professors at your university? All teachers anywhere?

Sure, my white privilege makes having a conversation in place of a grade sound great… because my privilege will help me get the upper hand in that conversation more often than not.

And then, even in a situation where you have a white male student and a white male teacher, the teacher is still in the position of authority… and not everyone feels comfortable with trusting all positions of authority. Often for good reason.

We keep talking about how grading is bad because we need to learn to trust students, but how dangerous is it to replace grading with something else that requires all students to trust all teachers at all times? What does it mean to force them to trust all of us all the time?

So does any of this make grading “good” by comparison? No, it still doesn’t. As many of my students pointed out, they still recognize that tests, papers, assignments, etc have problems, bias, and inequalities. But with a multiple choice question, you know the right answer is there. With a complex rubric, you know exactly what you need to do to get a good grade. Those questions and rubrics are usually problematic, but at least the answer is there – and you just have to learn the game to get the grade.

With a “conversation” about a grade – you don’t know the rules going in. You don’t know which teachers are harboring unacknowledged racism or sexism that will skew the conversation and hold you down. At least with a graded test, if they give you a lower grade because of racism and sexism, you can point easily to that corruption and say “I chose the right answer and you still marked it wrong!” or “the rubric line says 1000 words and I had 1112 and still got points taken off!”

As many students explained to me in many different ways: even though the white dudes will have advantages and privileges with many tests and assessments, those assessments are so cut and dried that there is a clear path for everyone to achieve equality (even if it comes at a greater price for people of color than for the white students). For some, a clear – but more difficult – path to equality can be more attractive than an unclear, unknown path through potentially dangerous conversations. Of course, not all found it to be more attractive, but it is certainly attractive to some. Those students are important voices to listen to.

Then, of course, there are the students that say they are used to grades, so they prefer to have them. They will even go as far to say they don’t see the harm in grades. Not a “good” reason to me… but who am I to say that is the wrong? Research backs me up? Or does it?

Let’s face it – it is really hard to research the impact of grades themselves apart from student opinion. How do we know that we are researching the grades themselves and not the assignment that produces the grades? How do we know that we are looking at grades and not bad assessment design, or even poor teaching of the topic being assessed? Or motivation, or privilege, or tardiness, or…. any number of issues that a “grade” could reflect? The biggest problem with grades is that so many factors go into them that we have a hard time really telling if the grades are the problem or if one of many factors that produced the grade is the real problem.

So that leaves us with looking at things like “student satisfaction” and “self-reported motivation” to tell if grades are a problem or not – which is not a bad thing. But once you go down that path, you have to be careful not to look at the results the wrong way. Too many times, educators see a study and assume the results mean that we know the one solution for all learners at all times: “this study found that group work is good, so let’s make all learners do group work!” Well, the study probably found something like “test scores went up 31% when group work was utilized” or “45% of students indicated greater whatever on such and such survey when group work was utilized.” Studies show averages and statistics – not something that is true for all learners at all times. Research is helpful, but rarely answers one solution for all learners. Educators have to rely on their judgement when making decisions on grading.

Therefore, whether we as teachers choose to grade or not to grade, we are usually centering the decision to be graded on our bias for or against grading, regardless of whether individual learners want it or not.

(What I say is that we need systems that allow for learners to choose how they get graded and by whom…. something we are working on with self-mapped learning pathways (aka dual-layer, customizable modalities, and all the other terms I can’t decide on… :) ), but that is post for another day.)

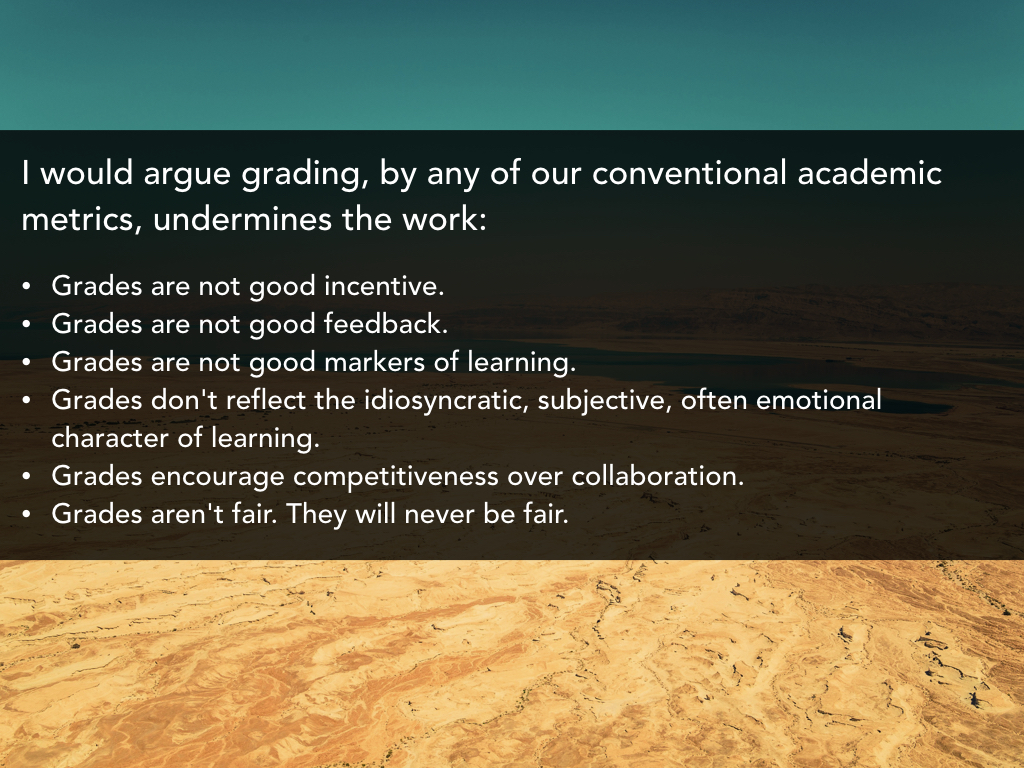

To be clear, I still find grades incredibly problematic. When I read a post like “Why I Don’t Grade” by Jesse Stommel, I completely agree. I also recognize that there are complications and other sides to many of these points as well. Just as a quick example of what I mean, I want to run through the graphic from this post that has probably been shared the most – not to disagree, but to extend the conversation (probably while repeating some of what was said in this post and others out there – apologies for that):

For example, its true that grades are not good feedback. This is probably because I can’t find much evidence they were ever meant to be “feedback” per se, at least initially. It seems that grades and feedback were meant to be separate but complimentary ideas at one time. The further back in time you go, the more likely you are to see grade-books and graded papers with separate feedback columns. But as society as devalued and de-funded education, you see grades replacing feedback as a means to cope with what society is doing to education. So is that really a problem with grades, or society? I would have to honestly point more at society.

Also, I completely agree that grades make a horrible incentive. They never encouraged me to study harder or lesser. But talk about a can of worms there – try discussing what is an incentive? with a diverse group of students, and you might end up with a heated argument. Everyone seems to find incentive in different things. Its a pretty relative thing in some ways (not in others, of course). But do some students really, truly feel that grades are a positive incentive for them? You bet. Do I disagree? Yes. But if I make my stance on incentive the default one for the entire class, what does that mean about my class? Who is the center then?

For the next one, again I agree that grades are not good markers of learning. But that is because they never really were meant to be markers of learning. Again, you go back in time, there was a greater understanding that grades were a representation of a learner’s ability to apply what they learned to an assessment or paper or what have you. But not as an actual marker of actual learning. There was a greater understanding (at least in older books) that learning was difficult to measure, and a grade was only evaluating the application of learning to an assignment or test. Through the years, many have lost sight of this. Many who champion grades have lost sight of this. Many administrators and policymakers and news-makers and so on have lost sight of this. Again, not the fault of grades but society.

This reasoning also applies to how grades are not reflective of the idiosyncratic, subjective, and emotional character of learning. I completely agree, but again, that is because grades are not supposed to reflect that. They just reflect how learners can apply the idiosyncratic, subjective, and emotional aspects of learning to specific tasks, assignments, assessment, and so on. Again, much of society has just lost sight of that, there by devaluing those aspects of learning to the point of barely acknowledging them in so many corners.

And then, I agree that we see a lot of competitiveness over grades – just look at the news. This is not a good thing. But where does this competitiveness come from? Most grades are based on a scale of 0-100% for a reason: they are supposed to reflect how close an individual learner got to perfecting the graded task (a problematic statement of it’s own, of course). Grades only become competitive when we put one learner’s grades next to another and compare them. That is another societal thing, and it is one of many major issues threatening education on all fronts. I know some people actually like that kind of competition, and I try to be understanding of that mindset. But I think that we can see so many quantitative and qualitative effects of that competition currently consuming education, that we can at least say that we should at least massively dial it back. But again, that is really a societal thing more than a grade thing.

On to the last one. This point is one that gets at the common argument in support of grades: objectivity. This is another one that is a huge can of worms once you get discussing it with students, as there are so many versions of “what counts as fair.” Some see grades as a way to make assessment fair, others see the problems with grading as making that fairness impossible. Really, when it comes down to it, our bias and other factors influence most arguments for or against various definitions of fair. So, unfortunately, the best we can usually come up with is “I think this is fair because I think it is so, and I think that is unfair because I think it is so as well.” We can lean on societal definitions and social contract, but history has proven that is not always the morally best option. Few or our positions are very defensible either way if we were to argue our case before an impartial observer.

However, I think within the “fairness” argument is a way to frame grades that objectively encapsulates one argument against grades that can’t be influenced by bias or context or the whims of society. One of the reasons grades are not fair is that a grade, by itself, does not tell you anything about how the learner earned that grade. You see an 80 – does that mean it was a perfect score that had 20 points taken off for being late, or a slightly above effort turned in on time by the learner? There is no way of knowing either way just by looking at a grade by itself. Educators mix so many things into grades – punctuality, following directions, context, format, etc – that by the end, any single grade is a reflection of all kinds of things in addition to how well the learner could apply their learning to an assignment. Then, if one adds up all the assignments in one class into an “A, B, C, D, E, F” grade… and then, add up all the class grades into a GPA… you end up with a number that really tells you nothing about the exact way that grade was determined. Whether you label that as fair or not, it is still a huge issue.

Of course, one could say that this issue is easily solved if we just add the ability for every instructor to input qualitative feedback to each grade. Have the instructor tell why that grade happened, and problem solved, right? Very true, but you would then have just eliminated the need for grades for anything other than competition – and no one cares about that competition after you have graduated. They only care about GPAs as a proxy for that qualitative feedback. But if they have it….

In other words, giving the explanation for why someone got a specific grade ultimately negates the need to have the grade listed in the first place.

![]() When one looks at all of my reasons and others’ reasons for not liking grades, so many of them can be written off by the “pro-grade side” (if that really is such a thing) as bias, taking grades out of context, historical misunderstanding, applying relativistic standards, or blaming grades for societal problems. And I still stick with my views on grades even though all of this is true, because you can’t easily separate all of that out even if attempting to “reform” or “fix” or “reclaim” grading. But at the end of all that, I still come down to the fact that a grade by itself doesn’t explain what it really means… and adding that meaning removes the need for the grade in the first place in the bigger picture of what really matters in education (because even if you like competition, you have to recognize it is not what really matters in the grand scheme of education). The main thing that we can do to best fix grades would make them obsolete, and that should say a lot.

When one looks at all of my reasons and others’ reasons for not liking grades, so many of them can be written off by the “pro-grade side” (if that really is such a thing) as bias, taking grades out of context, historical misunderstanding, applying relativistic standards, or blaming grades for societal problems. And I still stick with my views on grades even though all of this is true, because you can’t easily separate all of that out even if attempting to “reform” or “fix” or “reclaim” grading. But at the end of all that, I still come down to the fact that a grade by itself doesn’t explain what it really means… and adding that meaning removes the need for the grade in the first place in the bigger picture of what really matters in education (because even if you like competition, you have to recognize it is not what really matters in the grand scheme of education). The main thing that we can do to best fix grades would make them obsolete, and that should say a lot.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.

As a part of assessment, grading is often underdeveloped in that the goals of grading are not clear and at the forefront of teaching. Once you have clear goals that are being assessed, Messick’s (1995) validity framework can be helpful. That is, do theoretical rationales, empirical evidence, consequences of assessment practices and value implications align with teaching goals and values. Take the goal of motivation. Are there well supported and researched theories for how grades are used to increase motivation and do you grading practices align with the theories. Basically, do we understand how it works. Do other measures of motivation correlate with grading practices. What are the consequences from grading practices and do grading practices support the values that guide teaching. It sounds like grading is not meeting validity standards for you. Without validity, there is no justification for grading from a scientific standpoint. Creativity is needed but where to look?

Ellen Condliffe Lagemann’s historic analysis of education (An Elusive Science) notes that the history of education can’t be understood without understanding that Throndike won and Dewey lost, but also notes that it could have turned out differently. At least part of your dislike of grading may be because Throndike’s ideas (that still underly ed practices) are exceeding the limits of what they can accomplish and it’s time to relook at people like Dewey.

One of my favorite ideas about assessment is to orient it toward the future. Look out at the proverbial horizon to identify goals that can’t be seen quite clearly but has a reasonable chance of accomplished and state those goals in terms of the obligations and responsibilities of both the teacher and the student in work toward those goals. One might use a portfolio approach to record this journey. This could include memorization where needed or evidence of higher cognition or social accomplishments where appropriate. It can be individualized when needed, altered if evidence requires, and aligned with values and pedagogical theories.

What would be the largest objection, that the system is not set up that way. Again, the Thorndikian system is reaching its limits and it must be challenged on the basis of its limitations.

Messick, S. (1995). http://people.tamu.edu/~w-arthur/611/Journals/Messick%20%281995%29%20AP.pdf

Lagemann, E.C., (2000). https://www.amazon.com/Elusive-Science-Troubling-Education-Research/dp/0226467732

To be honest, this is really a line of discussion that goes back several steps before the starting point for this blog post. When I discussed the bigger theoretical conundrum of whether one should grade or not with my former students, it was always from the basis of validity and solid assessment design. That included fully developed goals, alignment with theories, motivation, etc. So the basis of this post starts with valid assessment techniques as the theoretical foundation, and I believe that is where Jesse Stommel’s began as well. I mention a few places in this post where problems in design or theory apply, but those are exceptions. My problem is not with validity standards, but everything else that starts once those are met. So you can look at the entire post as my description of my problem, or go read Stommel’s for even more details.

Leaving Dewey and Thorndike (and any other big names for that matter) out of the post was intentional, as I find both of them problematic in many, many ways. I haven’t really run into the whole “Thorndike versus Dewey” debate in a while, but I am aware that it still rages in some corners of academia out there. I see the outcome differently. Of course, I am – by far – not near as experienced or knowledgeable as many in our field, but after three degrees (two in instructional design) and several decades in education – I only see evidence of Dewey winning in our systems (or at least getting the most attention). And the education world is suffering for it.

Of course, even if I did see Thorndike winning, I would still say we are suffering for it. Whether Dewey or Thorndike “wins,” we all lose. Not that there isn’t a place for Thorndike or Dewey in some contexts – it’s that we don’t need one or the other all the time. We need both, as well as young whipper-snappers (comparatively) like Siemens and Downes. And other people like Fanon, Freire, Spivak, Cottom, Watters, Bali, Gilliard, etc. We don’t need winners or one person as the “winner” all the time – we need them all at different times for different reasons. Big names and small names, new and old.

We need this because we don’t need education to be centered on the teacher. When you speak of the teacher’s assessment goals and the teacher using grades to motivate and the teacher’s grading validity and so on – that is all centering education on the teacher. The learners become their lab pets: dependent beings that need to have learning “individualized” for them only to achieve the teacher’s goals. So I can’t fundamentally agree with a comment that centers the whole educational process on the instructor, with only one prevailing historical theorist to guide the way. At worst, education should be centered on learning itself; preferably it should be centered on the learner; at best, it should be centered on a learner learning how to become a self-determined learner (because there won’t always be a formal teacher or teaching process around). When we say that education needs Thorndike or Dewey or whoever to win, we are framing education on the teacher doing it all one way. That hasn’t been working for us in education, no matter who claims the victory.

Thanks for the comments Matt, let me see if I can clarify my thoughts. Sometimes my first pass leaves a little to be desired (and sometimes even the 2nd; I’m still learning which is why I comment).

My view on validity is summed up by the Davidson quote near the end of Jesse’s post. “There is an extreem mismatch between what we value and what we count.” In my thoughts, the conflict around grading also reflects this failure of measurement practices to support the outcomes we wish to achieve and what we value as educators. Messick was clear about this, and his words were even adopted as AERA validity standards, but the spirit of Davidson’s insight has been resisted at every turn. Why?

That brings me to Throndike and Dewey. I don’t use those names as citations, but as representative of two possible roads that education might have taken. Another way to say that is to ask, what is the background that facilitates how we think. I’ll use Lagemann’s example of the feminization of teaching at the turn to the 20th Century. It was thought at this time that women we’re incapable of serious thought and education must be organized around a hierarchy with male experts directing education. Women now occupy positions of power, but have we re-thought the foundations of how education is organized or have women just adapted to a male system. Think of how feminism failed to affect the sexualization of male power before the #metoo movement. Even Al Franken, a champion of feminist legislation could not escape the problems of male sexuality and power.

I salute the fact that you address bias and previledge. My primary point is, why does if feel that we have to fight the system to do this; or how has the system failed us by asking us to count what is so mismatched with what we value?

A little more (but still imperfect) account of the background to thinking here:

https://medium.com/@HowardJ_phd/what-is-science-and-scholarship-in-education-6e079f4564b5