Like many of you, I saw this Tweet about audio-only lectures making the rounds on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/sivavaid/status/1389592396820795397

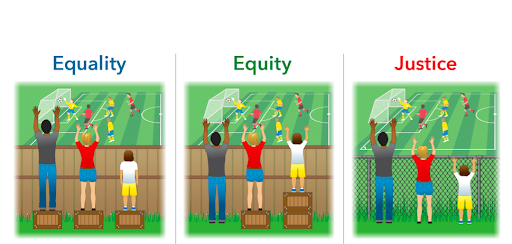

Now, of course, many questioned “why lectures?” (which is a good question to ask), but the main discussion seemed to focus on the content of courses more than lectures specifically. Video content (often micro-content) is common in online courses. There were many points raised about accessibility (both of videos and audio-only lectures). Many seem to feel strongly that you should do either video content or audio-only content. My main thought was: instead of asking “either/or”… why not think “both/and”?

From certain points of view, audio-only content addresses some accessibility issues many rarely consider. When creating video content, the speaker will sometimes rely on visual-only clues and images without much narration, leaving those that are listening with gaps in their understanding. So while it is easy to say “if you don’t want video, then just play the video in the background and don’t watch,” sometimes the audio portion of a video leaves out key pieces of information. This is usually because when the content gets to a visual part, the speakers often assumes everyone playing the video can see.

“Look at what the red line does here…”

“When you see this, what do you think of?…”

And so on. People that record podcasts often know they have to describe any visuals they want to use so people listening know what they are talking about. For accessibility purposes, we really should be doing this in videos as well. Not to mention that it helps the information make more sense for every one regardless of disability.

There are other advantages to audio-only content as well, such as being able to download the audio file to various devices and take it with you where you go. Some devices do this with video files – but how often do we offer videos for download? And what if someone had limited access or storage capacity for massive video files? Auio-only mp3 files work for a wider variety of people on the technical level.

On the other hand, there are times when video is preferred. The deaf or hard of hearing often come to mind. Additionally, some people think that the focus that video requires helps them understand better. Video can also help increase teacher presence. Plus, video content is not the same as a Zoom call (or even a video lecture broadcast live), so its not really fair to throw both in the same bucket.

I would also point out that just because learners like audio-only one semester, that doesn’t mean the next semester of learners will. And I would guarantee that there are those in Vaidhyanathan’s course that didn’t really like the audio-only, but didn’t want to speak up and be the outlier.

Remember: Outliers ALWAYS exist in your courses. Never underestimate the silencing power of consensus.

But again, I don’t think it takes much extra time to give learners the option to choose for themselves what they want.

First of all, every video you post in a course should be transcribed and closed-captioned as aground rule – not only for accessibility, but also for Universal Design for Learning. But I also know that this is the ideal that often not supported financially at many institutions. For the sake of this article, I am not going to repeat the need to be proactive in making courses accessible.

So with that in mind, the main step that you will need to add into your course design process is to think through your video content (which is hopefully focused micro-content) and add in descriptions of any visual-only content. Don’t forget intro, transition, and ending graphics – speak out everything that will be on screen.

Then, while you are editing or finalizing the video, export to mp3 in addition to your preferred video format. Or use a tool that can extract the audio from the video (this is also helpful if you already have existing videos with no visual-only aspects). Offer that mp3 as a download on the page with the video (or even create a podcast with it). Now your students have the option to choose video or audio-only (or to switch as they like).

Also, once you get the video closed captioned, take the transcript and spend a few minutes collecting it into paragraphs to make it more readable. Maybe even add the images from the video in the document (you already would have full alt descriptions in the text). Then also put this file on the page with video as a downloadable file. You could even consider maybe collecting your transcripts into PressBooks and make your own OER. However you want to do it, just make it another option for learners to get the content.

Anyways… the idea here is that students can choose for themselves to watch the video, listen to the audio file, or read the transcript – all in the manner they want to on the device they want.

One of the questions that always comes up here is how to make the video content sound natural. Spontaneous/off-the-cuff recordings can miss material or go down a rabbit-hole. Plus you might forget to describe some visual content. But reading pre-written scripts sounds wooden and boring. One of my co-authors for Creating Online Learning Experiences (Brett Benham), wrote about how to approach this issue in Chapter 10: Creating Quality Videos. You can read more at the link, but the basic idea is to quickly record a spontaneous take on your content and have that transcribed (maybe even by an automatic service to save some money). Then take that transcript, edit out the side-trails, mistakes, and missteps, and use your edited document to record the final video. It will then be your spontaneous voice, but cleaned-up where needed and read for closed-captioning.

To recap the basics points:

- Think about which parts of your video content will have visual aspects, and come up with a description for those parts in words.

- Record your video content with the visual aspects, but make sure to cover those descriptions you came up with.

- Create mp3 files from your videos and add that to the course page with the video embed/link and transcription file.

![]() If you want to go to the next level with this:

If you want to go to the next level with this:

- Enable downloading of your videos (or store them in a service that allows downloads if that option is not possible in your LMS).

- Turn your mp3 files into a podcast so that learners can subscribe and automatically download to devices when you post new files.

- Take your transcriptions and re-format them (don’t change any words or add/delete anything) into readable text, along with the visuals from the video. Save this as an accessible PDF and let learners download if they like.

- Collect your PDF transcripts into a PressBook, where you can add the audio and video files/links/embeds as well.

- Maybe even add some H5P activities to your PressBooks chapters to make them interactive lessons.

Matt is currently an Instructional Designer II at Orbis Education and a Part-Time Instructor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Previously he worked as a Learning Innovation Researcher with the UT Arlington LINK Research Lab. His work focuses on learning theory, Heutagogy, and learner agency. Matt holds a Ph.D. in Learning Technologies from the University of North Texas, a Master of Education in Educational Technology from UT Brownsville, and a Bachelors of Science in Education from Baylor University. His research interests include instructional design, learning pathways, sociocultural theory, heutagogy, virtual reality, and open networked learning. He has a background in instructional design and teaching at both the secondary and university levels and has been an active blogger and conference presenter. He also enjoys networking and collaborative efforts involving faculty, students, administration, and anyone involved in the education process.